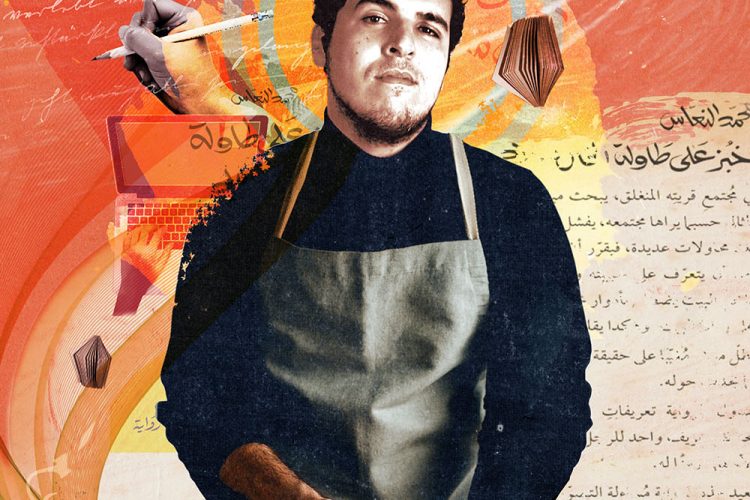

Like many, Mohammed Alnaas occupied himself during Covid-19 lockdowns by baking and writing. But the Libyan novelist came out of the pandemic with an International Prize for Arabic Fiction for his debut… and a new skill for making baguettes and croissants.

“Life in Libya can be stressful,” says the 34-year-old—IPAF’s youngest winner. “There are so many social interactions and responsibilities. We live very close to each other as people. So to have all the time in the world to write — and bake — was a positive, definitely.

“But let me tell you, baking a good croissant is very hard! It can take three days to make a good one. And when you do, you’re so proud.”

It’s an apt metaphor for Alnaas’s book, Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table. He spent the previous eight years on three manuscripts for books that were either not published or torn up. He kept going, not out of perseverance, but because he loved the act of writing itself. That comes across in a novel which Prof. Yasir Suleiman, chair of IPAF’s Board of Trustees, says is “sometimes wistful, always lyrical… the narrative carries the reader effortlessly through Milad’s journey, revealing his alienation from the norms of a society that values a manly interpretation of masculinity.”

“I adore that feeling of writing or reading a story. I feel like a totally different person,” Alnaas says.

Alnaas had always wanted Milad to be a baker—in the book he works through his perceived failure to become the ideal man by kneading bread. But it was only when Alnaas tried to bake his first batch himself that the novel opened up.

“It was almost like Milad was inviting me to listen to him. Baking is a time-consuming process and it demands patience, which then came through in my writing too. The novel got easier to write the more patient I was with it. The bread was like my teacher.”

Milad gets in trouble for being sensitive and kind; society is tough on him. “I wanted Milad to be sensitive, to be in touch with his feelings, not least because this is the opposite to how traditional views of men are in most Libyan writing,” says Alnaas.

An element of Libyan society has been tough on the country’s first IPAF winner too, since it was announced on May 22 that his novel had beaten five other shortlisted works to the prize.

“I got a backlash in Libya because writing about someone like Milad, who is different from the stereotype, is troubling for people. Radical even. There was so much going on it was impossible for me to write my next book,” he says, adding that he lived through 10 years of civil war in Libya, “so I think I will survive this!”

The IPAF—the most prestigious prize in Arab literature—raises books’ profile to Arab audiences, and to readers outside the Arab world too; IPAF winners get translated into English.

“What I’d hope is that this book gives people some perspective on what’s actually happened in Libya over the last 100 years,” Alnaas says. “An alternative history about the Libyan people themselves rather than the political conflicts that get all the international media coverage. You just don’t hear about ordinary people.

“And if they read my book, maybe they will discover or have already discovered other Libyan writers such as Hisham Matar or Ibrahim al-Koni; all I want to do is contribute to international dialogue, to give another perspective of how men and women live.”

Alnaas, who narrowly dodged death in the 2011 uprising, has simple hopes for Libya. “People have different wishes for how they want their country to be, but I think most want it to be stable, resourceful, to add something to the world,” he says.

“But it’ll take time to get there. Libyan people have been suffering since the 1920s. I’m still trying to find my way in the world. Even if people hate my novel, if they read it perhaps they will see all these different Libyan identities, these different notions of individuality and freedom. That’s my hope, anyway.”