The annual literary prize for British or British-resident writers of colour is a fantastic journey through work from writers of colour, and includes fiction, non-fiction, short stories, graphic novels or poetry.

The Jhalak Prize always has some brilliant work on its longlist and shortlist, but this morning’s announcement was particularly pleasing as it included one of my favourite books of last year, The Roles We Play by Sabba Khan. A moving graphic memoir exploring Khan’s family roots in Azad Kashmir and their migration to London, it’s a really intelligent, powerful look at the diaspora experience, her own struggle for self-acceptance and the role art can play in the “beautiful complexity” of life, as she puts it.

I spoke to Sabba for The National last May and I’ve posted the interview below. I really hope the longlisting gets this remarkable book the wider readership it deserves.

Also on the longlist is Huma Qureshi’s Things We Do Not Tell The People We Love, a short story collection mainly focusing on British women of Pakistani heritage grappling with family expectations or relationship issues. What Qureshi does so well in these tales is focus on tiny moments in a life which become formative.

“Really, what I wanted to to explore was this tension of emotions, of the secrets that people keep… and what happens when something absolutely terrible occurs!” she told me when we spoke late last year. What’s interesting is that the insensitivities and unkindnesses her characters often experience aren’t solely cultural. Race is not an overpowering characteristic in this collection, but a realistic underpinning of her characters’ lives.

Jhalak Children’s & Young Adult Prize

Was also great to see Radiya Hafiza’s Rumaysa, A Fairy Tale on the Children’s & Young Adult longlist. I spoke to her last April for The National about her fantastic take on the Rapunzel story; her hero, Rumaysa, starts off in the recognisable tower recognisable from Rapunzel, but then drops into another story to assist Cinderayla, finally helping Sleeping Sara find her freedom.

“I started imagining myself in Rapunzel’s shoes, trapped in a tower,” she told me. The wonderful guiding principle to her debut came quickly afterwards – “Rumaysa, Rumaysa, let down your hijab.”

But rather than simply amending these well-worn stories with names, locations and cultural references recognisable to South Asia, Hafiza embarked on something far more ambitious. These are retellings where not everything ends happily ever after, a Prince Charming whisking them away to save the day. These girls are heroes in their own right.

“The characters began to take on lives of their own,” said Hafiza, “and as they did, it became apparent that they could save themselves; they could make their own happy endings through their celebration of sisterhood and friendship.”

The shortlists for the Jhalak Prize are announced on April 19. I hope all these books are on it!

Sabba Khan

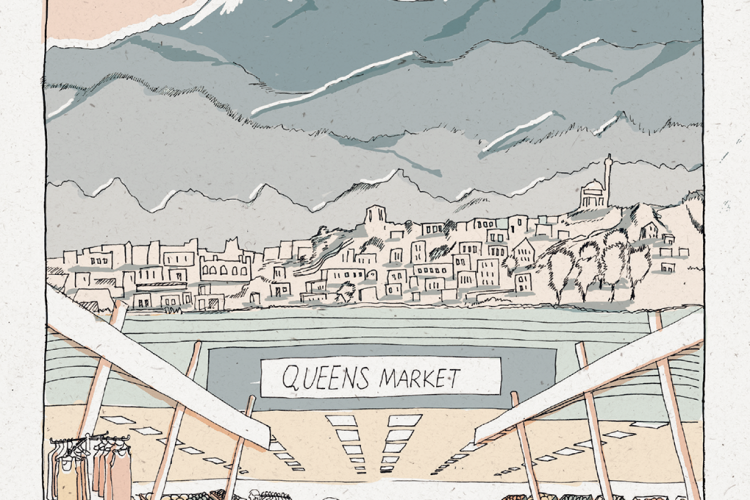

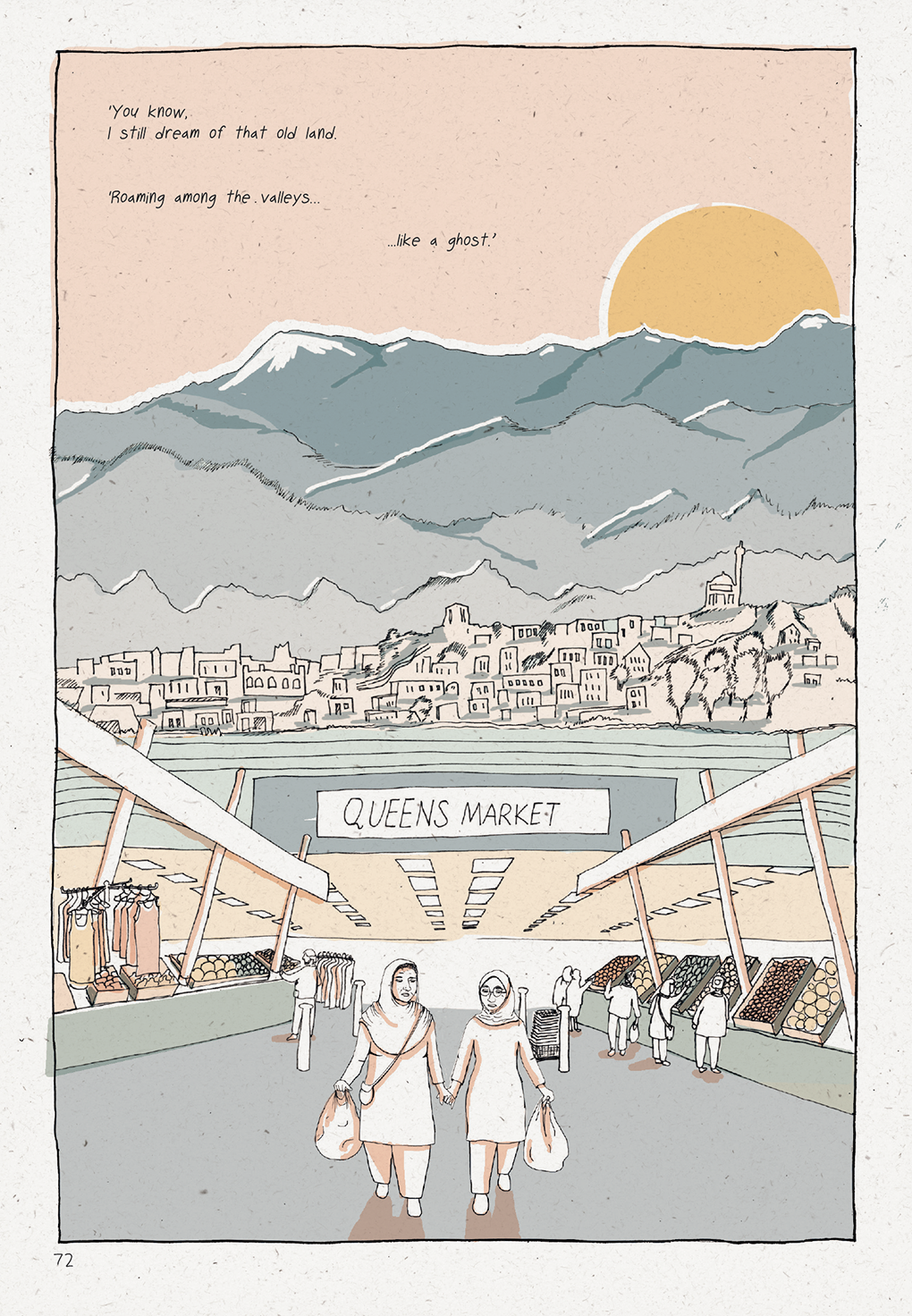

In the background, the sun sets over Himalayan mountains framing the intricately drawn villages of the Kashmiri valley, where Sabba Khan’s family are from. In the foreground, though, Khan is walking with her mother through Queens Market, in east London. It’s a telling juxtaposition, central to Khan’s moving graphic memoir The Roles We Play, the end of a chapter which starts with her asking: “Where is home, Mamma?”

It’s a question that is as much rhetorical and symbolic as it is literal. Two thirds of today’s British Pakistani diaspora can trace their origins back to Mirpur in Azad Kashmir, a place that suffered mass displacement after the Mangla Dam was built in the 1960s, submerging homes, lands and livelihoods. Khan’s parents came to England shortly afterwards, “doing jobs that the whites thought themselves above”. It was in London that Khan was born, the youngest of five children growing up dealing with ancestral ties and racial tension, the trauma of migration and the soothing – yet sometimes suffocating – balm of the family home.

It’s this constant push and pull between tradition and modernity, family and self-determination which gives The Roles We Play a poignant power. An architectural designer, Khan’s trade certainly informs her art as she interrogates the importance of space, both physical and mental, in emotive illustrations that range from comic strip-like narratives to sweeping panoramas, self-portraits and infographics.

If The Roles We Play feels like an extended, artistic therapy session, then that might be the point – although it’s also a universal, wry, exploration into the dilemmas, traumas and comforts that every child of immigrants will recognise. The accompanying playlist, featuring everyone from D’Angelo to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Radiohead, deepens the experiences still further.

“It started off as a personal exercise, and the more I showed the chapters to people, the more encouragement I got, the more I realised it could be a safe space to talk about things that are quite difficult to approach; my family, the diaspora experience, my own struggle for self-acceptance.”

Sabba Khan

Khan often likens her experiences to being one of constantly trying to please other people, whether that be her family, the expectations of the country in which she lives, or the Kashmiri Muslim community. She calls it code switching, and the book asks both her community and the country to look beyond racial stereotypes and expected behaviours.

“It’s important for my generation and the ones to come to give ourselves the space to ask what is beautiful and uplifting about our communities, too,” she says. “My aunt said to me, ‘Sabba, we are great explorers, we’ve travelled across many lands, we’ve accommodated so much, we’ve grown so much. We’re constantly adaptable.’

“And I see that in my own family. I’ve seen my parents start off bringing their children up in a very rigid structure of arranged marriages to the point where there’s me, marrying outside the Pakistani community. That just speaks to the fact that a lot of our communities aren’t closed off and segregated – we are highly agile, flexible, incredibly embracing.”

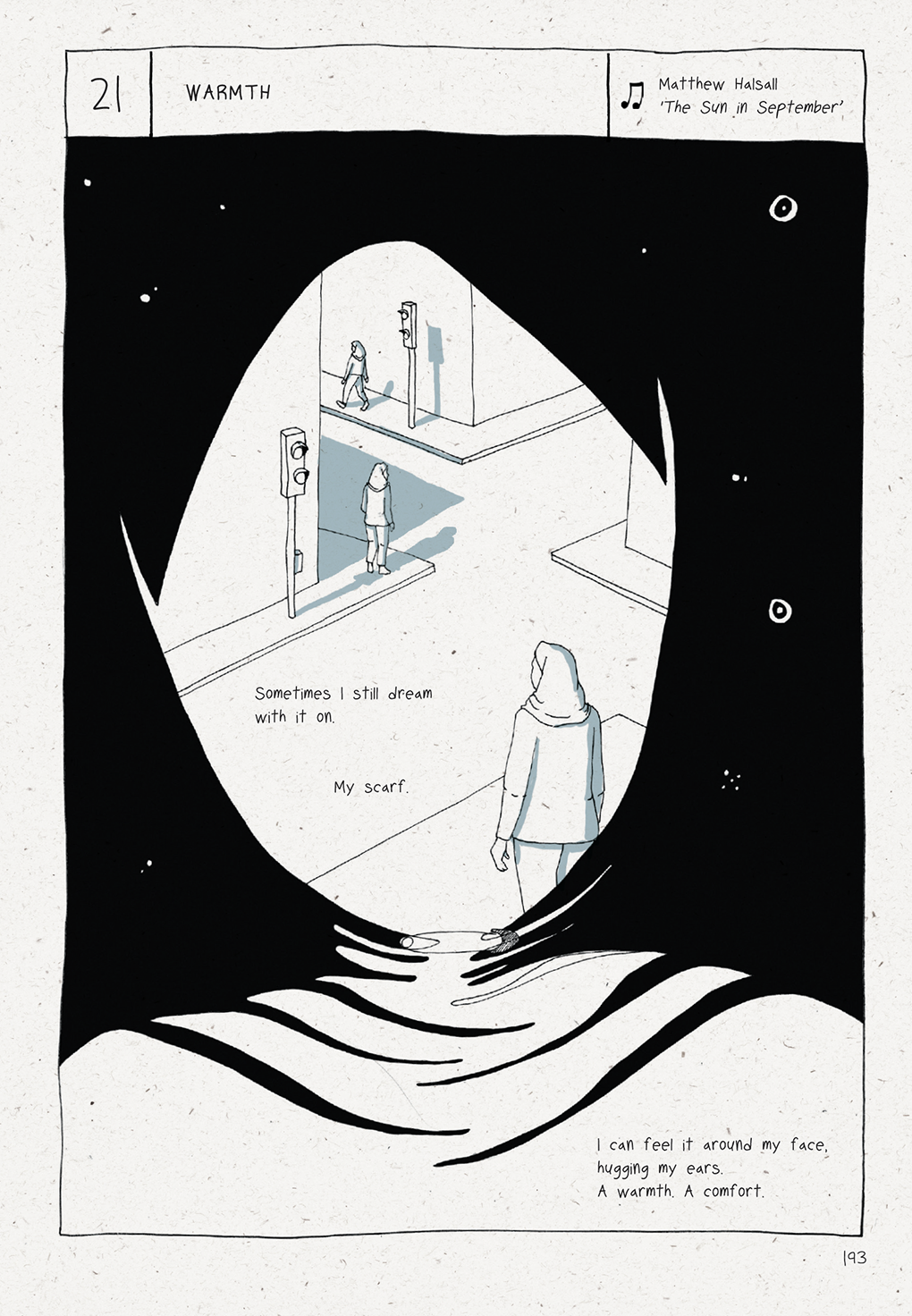

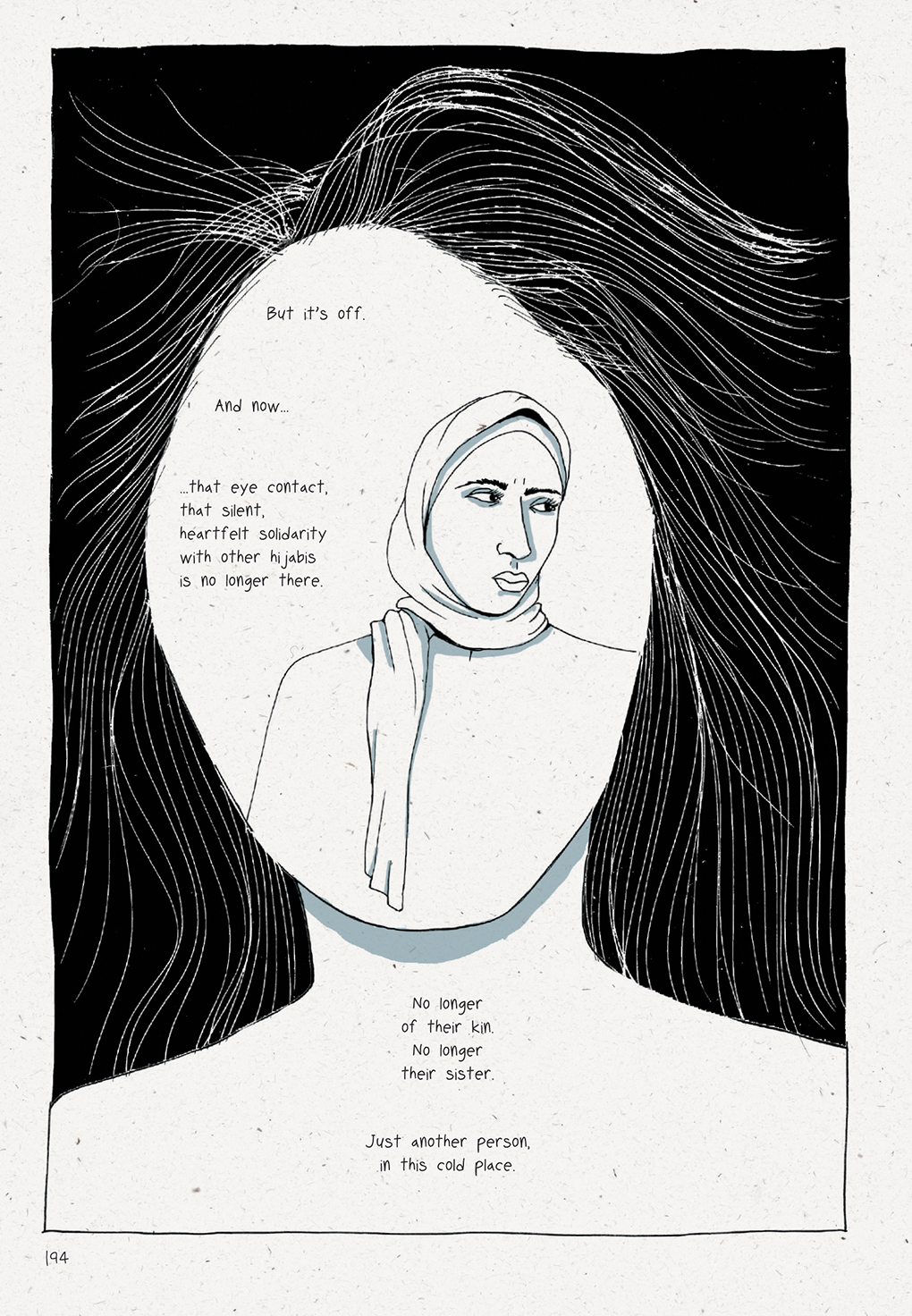

The beginnings of her relationship with her partner is beautifully explored in the book. There’s an intensely personal section where she not only realises the depth of her love for him – “who could have known that a temporal love of this world would bering me closest to the divine” – but also the jealously she felt because he, as a white man, was automatically “welcomed, accepted, loved and respected by everyone.” She wonders whether she would have met him has she not taken the decision to remove her hair covering in her twenties – “it had grown louder than me,” she writes – and knows that the answer is no.

“It was such an obvious symbolic gesture to de-pardah – maybe even a bit easy,” she says. “But I do hope that people are able to create those moments where they can define and position themselves in society in a way that works for them; it doesn’t have to be as visible as what I did.”

What The Roles We Play does explore really intelligently is that seismic decisions like de-pardah don’t immediately have to be binary; it’s not a rejection of religion, tradition or family as much as a chance to engender a deeper awareness of self.

“I mean, I was definitely on a journey of dismissing everything,” she admits. “But then, I’d also feel really uncomfortable and a bit disrespectful to everything that had come before me. There is a certain arrogance and self-righteousness in saying ‘all these people are wrong, I’ll show them the right way’. At every point I I would remind myself of the sheer power of what my family have achieved, and constantly remind myself of their context, their situations, the things that they were grappling with and how they’ve shaped and defined them.

“It’s almost like I am here, and able to critique things, and have therapy and these conversations with myself through this book because they afforded me that privilege. So definitely, spirituality and faith are an incredibly powerful tool to offer hope, a thread to hold onto when things are unpredictable, unreliable and unknown.”

The act of drawing has that power for Khan, too. She didn’t grow up with access to comics, but became intrigued by the graphic novel section of Central Saint Martins’ library, where she was studying architecture. She’s slightly embarrassed to admit that her gateway into the form was Craig Thompson’s best-selling Blankets, but actually the comparison is apt; both are in part about growing up in families in which religion plays a significant role, where the protagonist comes to some kind of accommodation with their relationship to spirituality.

That’s the beauty of The Roles We Play – a deeply human response to a situation in which, suffocated by the ‘othering’ of both her community and herself, Khan was constantly shape-shifting, trying to fit in, being judged. She broke the cycle through love, art and understanding.

“At first, I wanted people to cry with me and share in my pain,” she says. “Now, I want to give people a window to see into the beautiful complexity of life.”

The Roles We Play (Myriad Editions) is published on July 15. https://sabbakhan.com