Translator Yasmine Seale allows readers to not only understand the way the ‘One Thousand and One Nights’ stories were told, but why they must be told in this way

What’s your favourite story from One Thousand and One Nights? Of course, the usual answer would be Aladdin and the Magic Lamp, or Ali Baba and The Forty Thieves. Maybe Sindbad The Sailor.

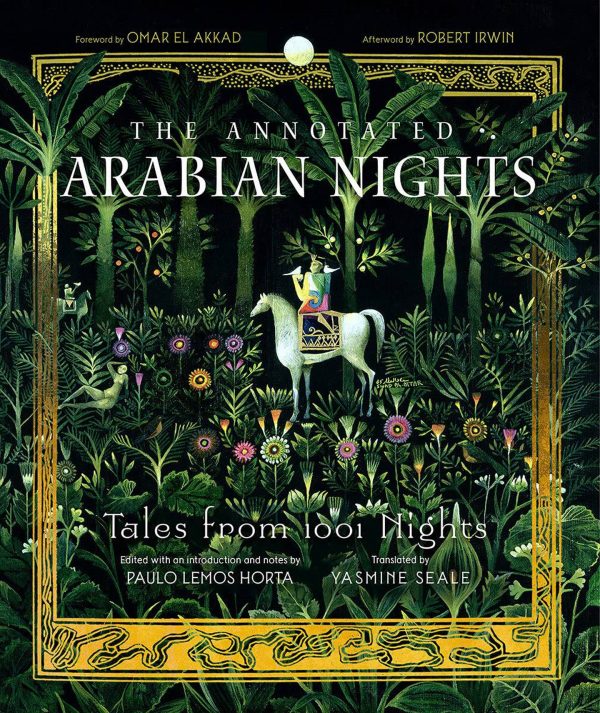

It probably wouldn’t be the mildly horrific tale of a young magician who feasts on corpses with her ghoul friend, and turns her husband into a dog when he finds out. Yet the inclusion and the treatment of The Tale of Sidi Numan in a sumptuous new translation, The Annotated Arabian Nights: Tales from 1001 Nights, sums up why this version may in time come to be the definitive reading of one the most important storytelling compendiums ever committed to print.

True, Sidi Numan gets similar animal-based revenge in the end. But in doing so, he’s learnt to see the world through the eyes of the marginalised and the oppressed. In the extensive margin notes which make The Annotated Arabian Nights such a joy, translator Yasmine Seale says that she wanted to make Numan’s wife less monstrous and more unreadable; it’s telling that it’s easier for Numan to believe his wife is supernatural than it is for him to try and engage with her. Which, ultimately, reflects rather less well on Numan than it does her.

So for probably the first time, The Tale Of Sidi Numan – and the 55 others that make up this collection – has been translated into English without prejudice. And by using a French-Syrian translator, Seale, there is definitely a feeling of “about time” to The Annotated Arabian Nights.

Not that the source stories are modernised or made more culturally relevant for 21st-century tastes. Seale doesn’t shoehorn in feminist references, she merely ensures that the female voices so often cut from Victorian translations are returned to their rightful place at the heart of these stories.

What this book shows time and time again is that it isn’t the stories themselves which are at fault; the way they were translated, and the preconceived ideas of the people who translated them, was far more problematic.

Novelist AS Byatt once wrote that though One Thousand and One Nights – or to give it the title closest to the original Arabic Alf Layla wa-Layla – appears to be a story against women, it actually marks the creation of one of the strongest and cleverest heroines in world literature. Shahrazad, the woman who is tasked with telling a story to the king each day to keep herself alive, should have equal billing in the English-speaking consciousness to her characters Ali Baba or Aladdin. Seale, and editor of this collection Paulo Lemos Horta, redress the balance with skill, subtlety and nuance.

Gender politics aren’t the only misappropriation addressed here. The National has spoken to Lemos Horta before about his lifelong work to ensure that a man from Aleppo, Hanna Diyab, gets proper credit for the magical elements to stories that were widely regarded as the figment of a Frenchman’s orientalist imagination. Antoine Galland produced the first translation of One Thousand And One Nights – Les Mille et Un Nuits – in the early 18th century. But actually, it was Diyab who was the source for the famous stories of Aladdin and Ali Baba, added by Galland later.

And if there’s a long-overdue recognition of Diyab here – a whole section is called Hanna Diyab Tales – there’s also the realisation that a lot of the Victorian translations into English were deliberately or insidiously racist.

Seale’s own background as a French and Arabic speaker makes her the perfect person to translate from both languages, and to ensure the Diyab stories themselves have a cultural underpinning that makes sense in the 21st century as well as the 18th.

In bringing all this together, Horta and Seale have produced something approaching the perfect Arabian Nights stories. They ensure that the less famous stories get their due. They emphasise that originally One Thousand And One Nights was far from being a compendium of children’s stories; it could be bawdy, bloodthirsty and brutal.

Through this book, we not only understand the way the stories were told, but why they must be told in this way; there’s unparalleled commentary and insight into the specifics of nearly every wonderful paragraph. Seale, too, strikes an impressive balance between poetry and prose; this is a huge yet accessible undertaking which is perfect to dip into.

With some fascinating illustrations and artworks, too, this 800-page book sits somewhere between cherishable story compendium, history book and cultural artefact. But what it does more than anything is emphasise the power and importance of storytelling to any culture.

These are tales that have endured because they are great, magical stories which capture the imagination, rather than because they are some kind of window into an exotic world. It’s this idea which The Annotated Arabian Nights really succeeds in conveying. Shahrazad is a fine teacher.