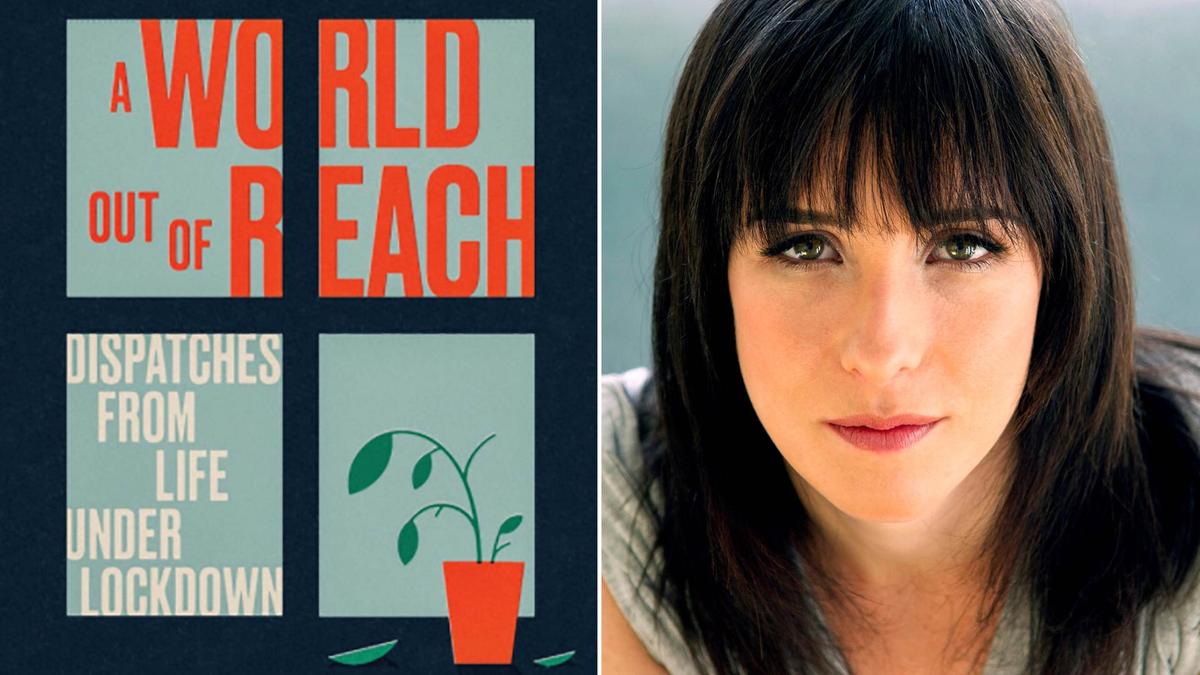

The collection shares the Covid-19 experiences of novelists, poets, historians, academics and physicians. The National, December 2020

When Meghan O’Rourke, editor of a powerful new collection of “dispatches from life under lockdown”, has to stop our Zoom chat to move somewhere quieter – her son has been sent home from preschool to isolate and they’re all in quarantine – we joke that it’s almost too perfect shorthand for her book A World Out of Reach. “Yes, that’s 2020 for you,” she says. “Chaotic.”

A World Out of Reach began life as the Pandemic Files earlier this year, an online project from The Yale Review that asked novelists, historians, physicians, poets, essayists, academics and scientists from around the world to submit writing that could in some way capture their experiences and thoughts as the Covid-19 crisis unfolded.

So in the first few pages of the book there’s an eerie short story from novelist Katie Kitamura that perfectly captures the creeping sense of dread in those early months. Meanwhile, gastroenterologist Nitin Ahuja adeptly combines the professional with the personal – “the sickness closes in” – and Alicia Christoff’s prose poem March 11 ends with a woman falling on the street: “Does she need help, can I touch her?”

Kitamura, best known for her 2017 novel A Separation, thinks that her piece, Do You Know Alex Oreille?, already acts as a window into her fears back in March, the gossip, the rumours and lack of knowledge which she explores as becoming like a virus in itself.

“It produced a series of behaviours that I think had as much to do with anxiety as they did with any epidemiological reality. It’s strange even just six months later to look back at the things we were doing in the spring – wiping down groceries, for example. I was in New York in April, and there was a period of several weeks when the sound of ambulance sirens was constant. Day and night. Now, even the sound of a single siren brings back a surge of anxiety.”

‘A World Out of Reach’ is a creative, thoughtful time capsule … Whether it’s a dusty artefact in years to come or something more valuable, is kind of up to us

Reading these entries as a whole is an initially sobering snapshot of a year no one will ever forget – but somehow there’s also great succour in the cumulative effect of this shared experience. “That’s how literature and acquisition of knowledge works, right?” says O’Rourke. It becomes a stay against fragmentation, chaos and uncertainty.”

Still, O’Rourke admits the early parts of the book – it’s presented chronologically – are chilling. She was heeding the warnings more than most; coincidentally, she’d been working on a book on viruses and their after-effects.

“I’d been in touch with all these virologists who were telling me: ‘This is going to be a pandemic, get to the grocery store, and slowly and calmly buy toilet paper and rice,’” she says, with a laugh.

“One thing the book really conveys is that period was almost like a cognitive test: we were trying to come to terms with something that was clearly going to change the world, while not being quite sure how dramatic and drastic that would be. And then, when it was drastic and we did go into lockdown, getting used to living with fear and anxiety was really tough.”

O’Rourke thinks writers dealt with those fears through the act of writing itself. Khameer Kidia is a Zimbabwean physician and writer living in Boston, and he certainly feels that his piece, Lives Or Livelihoods, “helped crystallise my thinking and emotions. This year in particular, writing has been important for me to cope.”

Kidia’s entry is also an important challenge to readers caught up in their own literal bubble this year. Rather than focusing entirely on the response in his hospital in Massachusetts, he ponders how his family, friends and colleagues in Zimbabwe are coping with a health system where “the capacity to cope with even minor upsets is limited. It’s disheartening to think I’ll likely get the vaccine long before my mother or sister do.”

It’s not controversial to suggest the early sense of everyone being in this pandemic together quickly gave way to inequalities being exacerbated, and in Kidia’s emotive piece this is laid bare. “Covid-19 has revealed for many what some people have always known,” he says. “In my hospital for example, nearly all the patients with Covid-19 who I cared for in the ICU were Black or Latinx. Yes, there is an opportunity to use the pandemic to advocate for change, but I’m a little pessimistic about the world order, and just how much it cares about the violence of structural racism and colonialism.”

Still, time and again in A World Out of Reach, writers grapple with that exact quandary – how much the coronavirus might have changed us. The last line of Katamura’s short story is: “It was not the same world as before.” Or, as O’Rourke puts it more hopefully: “Having lost the world, we might be able, suddenly, to see it anew.”

Ahuja, an assistant professor of clinical medicine in Pennsylvania, says: “It’s a surreal experience to know you’re in a world historical event as it’s happening.” His piece is a tribute to how his father would explain to his Hindi-speaking grandmother that her nursing home no longer welcomed visitors: bimari hai bahr, There’s a Sickness Outside.

“Almost certainly this will leave a mark,” he says. “I can’t forecast what that will be, but my hope at least is that the many critiques that have emerged will lead to some form of rehabilitation for us all.”

When Ahuja re-read There’s a Sickness Outside a few months ago, he admits that it made him feel uncomfortable. His fears – “the air around us goes foul … I’m fortifying barriers between myself and everyone I love” – seemed, to him, “histrionic, maudlin”.

READ MORE

‘The Lonely Century’: Why the past 20 years have been ‘uniquely’ isolating, even before isolation of pandemic

‘Electric News in Colonial Algeria’ wins prestigious academic book award

How Ravinder Singh harnessed personal tragedy in bestselling novel ‘I Too Had a Love Story’

But like so many of the pieces in the book, they are a powerful and important record of how people felt, how professionals approached a new coronavirus and the sacrifices they made, all too easily forgotten or taken for granted now that we know a little more about the virus – or are tired of it.

“Actually, as we experience a second surge in the US, it brings me back to that headspace of uncertainty,” he says. “I’ve written some more since I spent some time in a Covid testing tent, and it’s been a way to process and distil my thoughts and use them to figure out what’s going on. I suspect we will get through this, but the cracks in the structure of the system that allow for the situation to get out of control are still there.”

A World Out of Reach is a creative, thoughtful and hugely readable look at the way we live our lives in the third decade of the 21st century. A time capsule, perhaps. Whether it’s a dusty artefact in years to come or something more valuable, an agency for change, maybe, is kind of up to us.

“While the future will assess the ways we failed each other, or the economic fallout, or how we demanded change, what this book does is look at what all that felt like in the moment,” says O’Rourke. “And this moment, this pandemic we’re living through, says everything about who we are as people.”

Extracts from ‘A World Out of Reach’ can be read at