When Belgian cyclist Charles Deruyter crossed the finish line in the third stage of the Circuit des Champs de Bataille, he fell into the arms of his wife and began sobbing. His bike had two flat tyres. He was too cold to hold the pen to sign in, “an unspeakable mud-man” who had, over the 323km between Brussels and Amiens, become a pitiable sight. Cycling champions such feats of physical and mental endurance; they are the stories which fuel its appeal. But what Deruyter had experienced was far more elemental than that. In the past 18 hours, he’d seen a vision of hell itself.

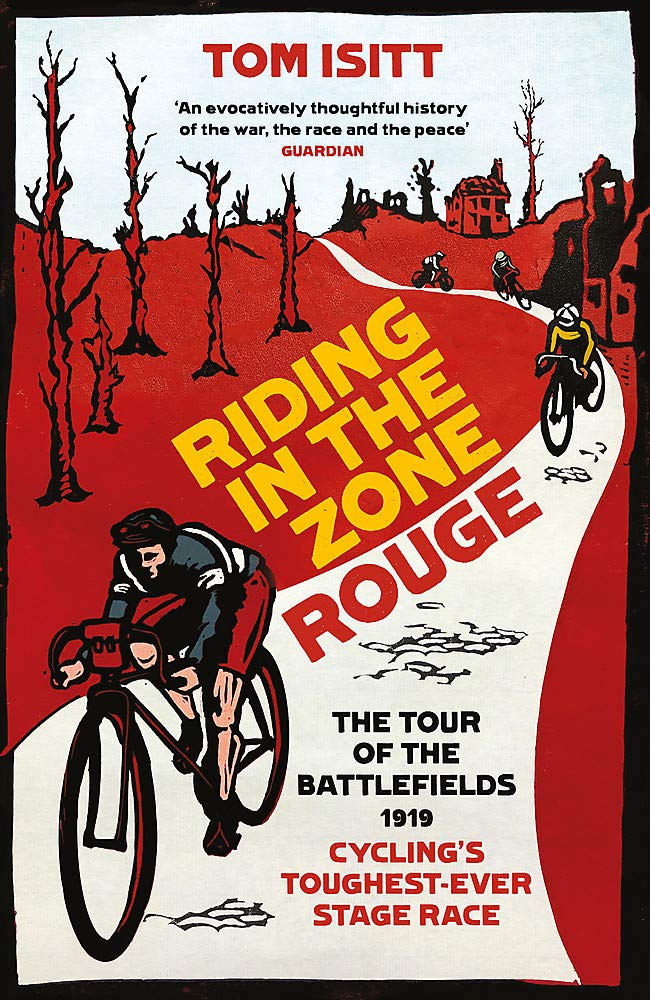

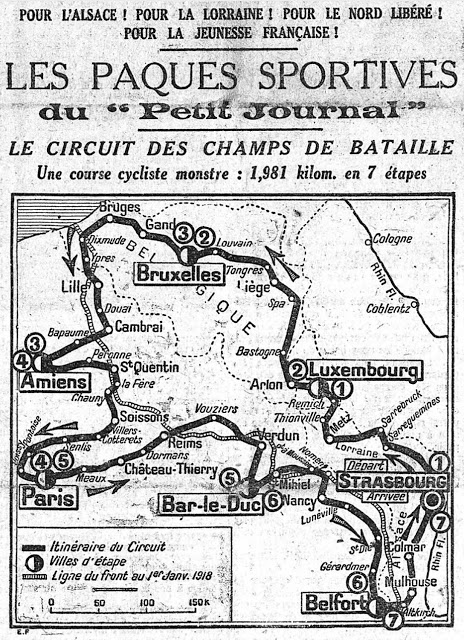

“All around the riders was churned-up chaos,” writes Tom Isitt in Riding In The Zone Rouge, his poignant, fascinating account of an extraordinary stage race across the battlefields of Belgium and Northern France just a few short months after the First World War had ended. Despite broken roads and scenes of utter devastation, French newspaper Le Petit Journal planned “une course cycliste monstre; 1,981km en 7 etapes” that started and ended in Strasbourg. It was a “monstre” too – and it’s not clear whether the entire route was actually reconnoitred beforehand.

One journalist at the time said the race was “inhuman.” Riders had to pick their way through a Dantean vision of hell, where fields were still peopled with shattered corpses. “A dank, rotting smell of death and mud and rust oozed from the lifeless soil,” writes Isitt – and many of the riders climbed off mid-stage, exhausted, and slept rough in these dug-outs and trenches on the battlefield. And then, incredibly, carried on.

So Riding In The Zone Rouge – which has been deservedly shortlisted in the cycling section of this year’s Telegraph Sports Book Awards and is just out in paperback – has both a figurative and literal meaning. The 87 riders were pushing themselves way beyond their physical limits in stages which started early and often finished in the middle of the night. Mentally, this was a race which asked more of a rider than to just keep going. They were passing through places they knew, had grown up in or won races in, now totally destroyed. Through battlefields they had sometimes served in, “surrounded by the ghosts of the thousands of men who fought and died in this abysmal landscape.” They were in their own very personal red zone.

And literally too; the Zone Rouge was a 1,200km area of northern France so badly damaged by gas and shells that its government declared it not fit for habitation or cultivation – though still somehow acceptable for a bike race to ride through. Intriguingly, areas of the Zone Rouge still exist today, evocative places that remain out of bounds due to fears of unexploded ordnance and poisoned soil. Exploring these places, 100 years on, is one of the reasons Isitt himself rides the route – or a version of it – himself.

Attempting to recreate epic quests of yesteryear has become an oft-used trope in cycling literature – most notably by Tim Moore. In Isitt’s case, it really works. Not because he tries to emulate back-to-back 300km stages. Far from it: after cracking three ribs on a bike path he has to abandon, and continue his tour of the battlefields later in the year. But doing this journey on a bike 100 years later means Riding In The Zone Rouge becomes more than mere history; as Isitt muses, there is something unique about the way cycling enables you to look at the world in a slower, quieter, more considered way. Two wheels are perfect for a journey through such a solemn, evocative landscapes, a contemplative starting point for some fine writing placing a war fought a century ago in contemporary contexts.

This combination of well-researched history, sporting achievement and travelogue is well balanced, added to by Isitt employing his own small amount of “literary licence”; he imagines conversations between horrified riders in cafes after gruelling stages. It’s a gamble – one of which I was initially wary. But as the layers of this story build, it begins to make sense, not least because it again speaks to the idea of cycling’s history being intrinsically tied with imagination and storytelling.

The Circuit des Champs de Bataille was never raced again – it was too hard, badly organised and overshadowed mid-race by both the Treaty of Versailles and some of the big riders of the time choosing the relative comfort of track racing. Still, as Isitt learns from his own experiences riding past countless memorials, graves, trenches, battlefields, the idea that this race could have been an annual reminder of the futility of war and the sacrifice of millions has much merit.

In 2018, the Great War Remembrance Race was organised by Flanders Classics with high hopes of doing just that, in a one day format. Won by Estonian Mihkel Räim, it only lasted a year, and the subtitle of the Gent-Wevelgem’s race, “In Flanders Fields”, returned to being the only overt nod to the history of a land in which riders make their names year after year.

For now, then, it’s Riding In The Zone Rouge which offers a startling reminder of our capacity for destruction and heroism, despair and resilience. It took 100 years and Isitt’s book; Le Circuit Des Champs Bataille might not just be “cycling’s toughest ever stage race,” but its most instructive too.

Riding In The Zone Rouge (W&N) is out in paperback now. Buy now from Waterstones