Emirates Open Skies, April 2020

There’s a spectacular moment in Sir David Attenborough’s new film A Life On Our Planet where the camera tracks a herd of animals across a wide plain. It looks like an awe-inspiring natural phenomenon – and it is – but the shot also holds a hidden message. “The thing is, there used to be millions of, say, wildebeest or caribou in these migrations,” says Gavin Thurston, the director of photography responsible for these incredible images – which sadly we’ll now have to wait until the autumn for after Coronavirus led to Netflix postponing its cinematic and televisual release this month. “Now it’s down to 700 animals because they’ve been hunted. It’s tragic – we’re destroying all these amazing things.”

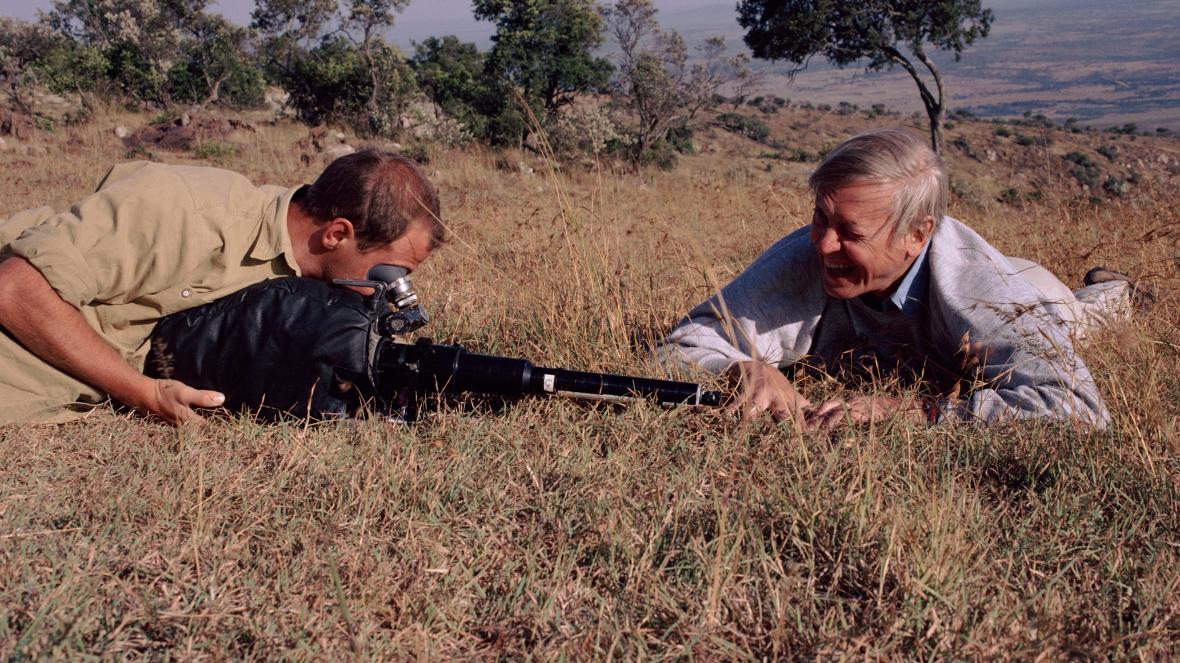

Thurston should know. Over a long and spectacular career behind the camera he’s travelled across the globe, to all continents and both poles, to create some of the most seismic, important and well-loved nature programmes of all time. There have been Emmy nominations for Our Planet, Blue Planet 2, Frozen Planet and many more. He’s witnessed first hand the changes to our natural world in that time – and in the foreword to Thurston’s new book Journeys In The Wild: The Secret Life Of A Cameraman, David Attenborough himself admits that humanity is at a crossroads.

For Thurston, that Attenborough has become so outspoken – the film also asks us to think about acting now to put the climate emergency right – says it all.

“David’s approach to wildlife film-making was previously always that you couldn’t lecture people, you couldn’t tell them what they must or mustn’t do,” says Thurston, fresh from a trip to an Antartica which has just recorded a record high temperature. “Our belief was that you show people these amazing things and places with huge passion – and then hopefully that passion rubs off onto the viewer. Put simply, once you care about an elephant, you are not going to put up with the ivory trade.”

So now, in A Life On Our Planet, Attenborough couldn’t be clearer. “The way we humans live on earth is sending it into decline,” he says in that inimitable voice.

Maybe Attenborough’s change of heart comes from the knowledge that huge nature programmes are genuinely having an effect. When Blue Planet II broadcast its harrowing images of albatross feeding thrown-out plastic to their chicks in 2018, research found 88 per cent of people who watched the episode changed their buying behaviour regarding single-use plastics. The UK’s environment minister at the time was haunted by the images of plastic bags in another episode.

“I feel pretty proud that the television I’ve worked on has changed policy and changed the culture almost overnight,” says Thurston. “Using a plastic straw is about as socially unacceptable these days as lighting a cigarette up in a shopping mall. What I would say is that we have the solutions to fix a lot of environmental concerns; we have solar, wind power, we know to eat less meat, not to waste or chuck plastic in the ocean. We just all need to agree on it.”

Journeys In The Wild is, as well as a wonderful adventure story, a fascinating insight into the work of a wildlife cameraman. The craft itself has changed as much as the natural world it depicts – as have expectations. When Thurston says they’re competing with the biggest brands in entertainment, he’s not exaggerating: Our Planet was up against Game Of Thrones and Veep in the Primetime Emmys last year.

“The cinematography has got better and better,” he admits. “We were still trying to emulate cinema 20 years ago but it was much more difficult. Now we have cleverer tools – we can track hunting dogs as they race across the plains, fly with flocks of geese through the air – it’s easier to take the viewer on a journey now. Before we had to stop, get the tripod out, put the camera on… it was so different.”

And that commitment to excellence extends to deep behavioural science; obviously you can’t script how a bird will lay and look after an egg but Thurston reveals that if a series takes four years to make, the first year is entirely taken up with research and preparation.

“Actually, you pretty much know what’s going to happen,” he admits. “One thing in our favour over an HBO drama is that although they can try and fabricate beautiful shots, what we’re filming is the most beautiful thing ever; the natural world in natural sunlight. All of us have a connection with nature but not all of us have a connection with Game of Thrones.”

Which is not to say Thurston’s job ever becomes predictable or run-of-the-mill. He remembers getting up in the morning to film the five million-strong cormorant colony in Peru for Our Planet and finding it ‘just mind blowing, extraordinary…. and imagine there used to be 50 million of them!

The idea that you have to have limitless patience to be a wildlife photographer doesn’t wash with him either.

“What I’m doing and seeing, very few people on the planet get to do, he says. “All these amazing spectacles and places. I mean, I must have been to Kenya 30 times and each time is an absolute joy. I actually get more impatient with people!”

Including those who complained that the camera crew who saved a family of emperor penguins in the BBCs Dynasties were somehow interfering with nature. There is a fine line in depicting the natural world and interfering in it, but Thurston says he would have done exactly the same.

“Look, there was a natural snow bowl from which these penguins couldn’t escape. These cameramen were witnessing a whole load of penguins about to die. So they trod a path down and the penguins used it to get out. I can’t understand why that caused so much controversy; they made a judgement call and let’s be honest, helping a few penguins doesn’t even scratch the surface when compared to the impact humans have had on them.”

Which brings us back to a cameraman’s responsibility to show the natural world as it is. More so than ever, Thurston feels that keenly.

“Dramatic images have an impact; they’re powerful and they provoke thought in these heightened times where we have a responsibility to the planet,” he says. “I’ve still got confidence that human beings are not so stupid that they can’t see we’re knowingly sawing through the branch we’re sitting on.”

Gavin Thurston was talking to Emirates Open Skies at the Emirates Airline Festival Of Literature. Journeys In The Wild: The Secret Life Of A Cameraman is out now.