It’s a hugely thought-provoking tale about the Mexican immigrant experience in the US. A book that’s already been feted by major critics and caused some debate about how migrants cope with the constant feeling of being watched, appraised, feared even. But this isn’t Jeanine Cummins’ controversial bestselling thriller American Dirt, backed by the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Stephen King – and then swiftly criticised for being “conspicuously like the work of an outsider”.

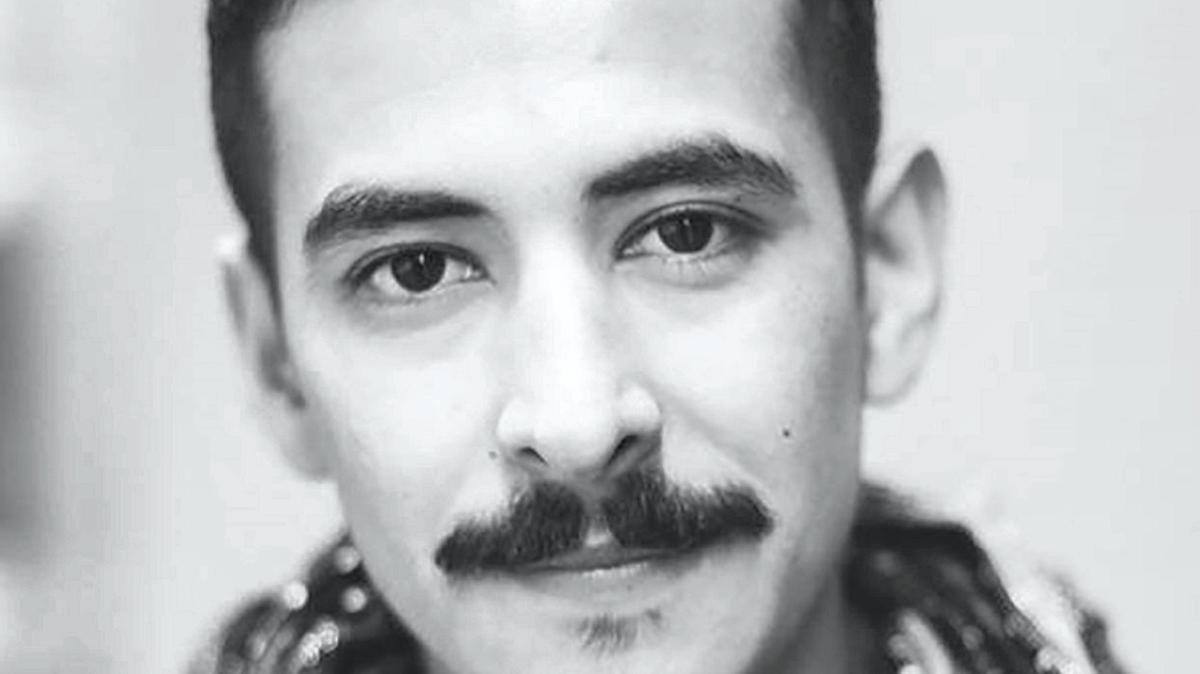

Instead, Children of the Land by Marcelo Hernandez Castillo – a poet whose family were firstly citizens of Tepechitlan, Mexico, then undocumented residents of the United States – is an infinitely more powerful, grounded and honest depiction of life as a migrant.

“There were so many cultural oddities I wanted to explore; my family’s life, my life, what the country was like for me…” Castillo says of his traumatic but urgent memoir. “So I started writing and these long-lasting effects of our encounters with immigration kept coming to the surface.

“There’s this constant surveillance and that feeling never goes away; if anything undocumented people in the US are actually over-documented. You don’t live in the shadows, you actually put yourself in the system so that your court case can be adjudicated. You’re hyperaware and hypervigilant of how visible you are.”

Castillo, talking from a Los Angeles beach as his family plays in the background, takes a deep breath when I ask him how he feels about Cummings’ book. You’d forgive him for being a bit weary – or wary – about the question; after all, he can barely go anywhere these days without people asking his opinion of American Dirt.

Which is unsurprising – Cummings, who isn’t Mexican, admits in her afterword that she “wished someone slightly browner than me would write it”. Latina writer Myriam Gurba criticised Cummings for her “overly ripe Mexican stereotypes”, for prose “taint[ed]” by the “white gaze”. Latinx writers formed a coalition called #DigidadLiteraria to “combat the invisibility of Latinx authors, editors and executives in the US publishing industry”. Winfrey, in a hasty about-turn, has just filmed a “deeper, more substantive discussion” about the book for her Apple TV+ show next month.

“It’s, er, interesting. I’ve been working on and through these themes, these issues of immigration my whole life – and there’s a quote from Jeanine where she says that she’d been working on American Dirt since 2013, when immigration was starting to become relevant. And I’m thinking well, ‘to you, yeah, but my family have been making these journeys for 100 years, my children will continue, after me, to engage with the immigration system in some way’. “I wrote my book in complete ignorance of hers, in fact I didn’t know anything about it until maybe a week before people in literary circles called it out. I guess the difference is that I didn’t intend to write a story about everyone in the way that I think she does.”

Castillo is right, but actually his book achieves that rare feat of making the personal become universal. It’s impossible to read his stories – the fractured relationship with his father who was deported back to Mexico or the threatening visits from immigration agents when Castillo was a teenager, without wanting to physically do something, and Castillo admits that one of his hopes from the book is that people feel moved enough to donate actual money to trusted organisations working in immigration.

Conversely, the problem with American Dirt, for Castillo and others, is that it allows white liberals who are its overwhelming audience to be thrilled and maybe moved by the narrative, yet feel that they’ve done enough by the simple act of reading it.

“Someone told me that Children of the Land made them feel uncomfortable, and I said ‘good’,” Castillo says. “I didn’t enjoy writing this book, I never want to do it again – I realised how much trauma I’d blocked out of my life.”

In fact, Castillo admits his memory is now terrible, so the flashbacks in the book are more aesthetic, lyrical gestures, a residue of his career in poems perhaps but also lifting this memoir into much more interesting territory.

“What I didn’t want to do was sensationalise an event or any violence,” he says. “That ‘if it bleeds, it leads’ mentality that newspapers have really isn’t what this book is about. I wanted to look at the minute, inward emotions. If your threshold for empathy is decapitated heads then you’re asking people to hurt again and again. But if I can set it low so that the smallest kind of pain stirs something in you then I think I’ve done my job.”

Castillo is also keen that people understand from Children of the Land that governments – and not only the American government – often treat immigrants as expendable. Castillo has been granted a green card, and supposedly now has a stable, more predictable existence, but he still wonders “how much more I could have done with my life if I’d been spared the energy it took to survive.” Many of his friends who he grew up with are in prison, dead, or have not been able to live up to their full potential.

Castillo, although he probably wouldn’t say so himself, has certainly been able – through hard work, torment and struggle – to make good on his ability. The endorsement for Castillo from Myriam Gurba herself says it all. She wrote last week that if you really want to understand Latinx culture, then Children of the Land should be on your list. Put that on your show, Oprah.

Children of the Land is published by HarperCollins