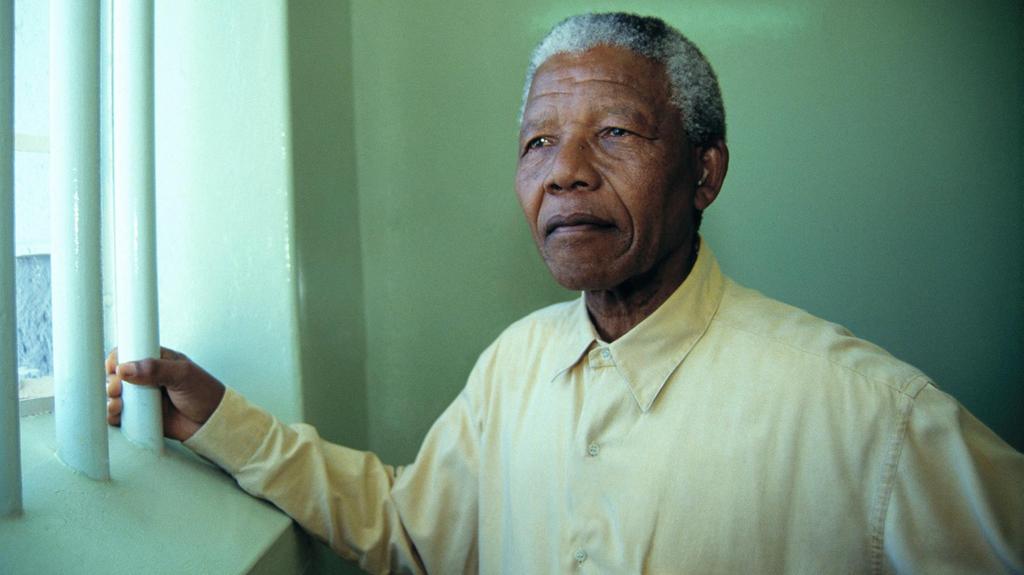

In a cell 2.4 metres by 2.1 metres, Nelson Mandela sat down to write to his daughters. It was 1969, and Mandela had been serving a life sentence as a political prisoner on the maximum security Robben Island in South Africa since his youngest, Zindzi, was 18 months old. She was now eight. Conditions had been brutal; Mandela was only allowed to write and receive one letter every three months.

“I do not know, my darlings, when I will return,” he wrote. “It may be long before I come back; it may be soon. But I am certain that one day I will be back home to live in happiness with you until the end of my days. Do not worry about me. I am happy, well, and full of strength and hope.”

That Mandela could be any of those things in a place where, initially, ‘bed’ was a mat on a concrete floor, hard labour was the norm and there was little prospect of release, is remarkable. But The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela – an authorised collection of correspondence with family, compatriots, officials and apartheid authorities spanning his 27-year sentence – reveals the incredible resilience, defiance and human spirit of one of the 20th century’s most inspiring men.

The letter to his daughter – whom he wouldn’t see for another eight years – appears just a few months after Mandela is forbidden permission to attend his mother’s funeral. Some of the most profoundly moving letters are from this time – particularly when his eldest son Thembi then dies in a car accident. He can’t associate a “lusty lad” with death, muses on “the psychological strains and stresses my absence from home had imposed on the children” and mourns that he wasn’t able to persuade Thembi personally not to ditch his studies and become a driver.

And yet, in a letter about the tragedy written to his second son Kgatho, he manages to write: “It is never wise to brood over past calamities, however disastrous they may appear to be … work harder on your studies, never allow yourself to be discouraged by difficulties or setbacks, and never give up the battle even in the darkest hour.”

This would sound glib in the hands of almost anyone else. Mandela was in his own darkest hour, not least because he found out months later that not one of his letters offering succour and comfort to his family had made it out of Robben Island. “I hope that the invisible forces responsible will be prompted by considerations of fair play and sportsmanship to give me a break and let this one through,” he says, remarkably generously, to his sister-in-law.

If Mandela knew that many of his letters might not reach their intended addressee, he also understood that they could still be important – not just for his own sanity, but because censors and people of influence would read them. Perhaps that’s why they’re not often angry missives railing against authority. The fury comes with his impotence in a cell. When his wife Winnie is imprisoned and persecuted he tells her: “I feel as if I have been soaked in gall, every part of me, my flesh, bloodstream, bone and soul, so bitter am I to be completely powerless to help you.”

Still, Mandela mostly comes across like the saintly, patient and reasonable man that has now passed into South African iconography. The calm requests for reading glasses that characterise the first phases of the collection, or the letters about the studies he wanted to complete, seem perfectly normal. So normal, in fact, it’s tempting to skip them. But their sheer number layer into a larger point; that for Mandela himself, reading and education were perhaps more important than all his political ideals.

But they were ideals that, via his words and actions, managed to change the world. His writing restrictions were eventually loosened, and there’s an argument that the conciliatory (but never submissive) tone of his letters to authority perhaps contributed to the regime’s softening stance towards apartheid and Mandela’s eventual release. The letters make it clear that Mandela wasn’t a feared political prisoner set to sabotage the country in 1990, but a thoughtful statesman who, as as far back as 1967, was writing to The Department of Justice and dreaming of “a democratic government in which all South Africans, irrespective of their station in life, of their colour or political beliefs will live side by side in harmony”.

That Nelson Mandela ended up president of a country that eventually signed up to that dream is still one of the most incredible stories of our time. These letters are an invaluable insight into how Mandela turned a solitary existence into a powerful movement for good, and how optimism, hope and truth – even when faced with the darkest of situations – can still make a difference.

How we need a Nelson Mandela in 2018.

The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela is out now