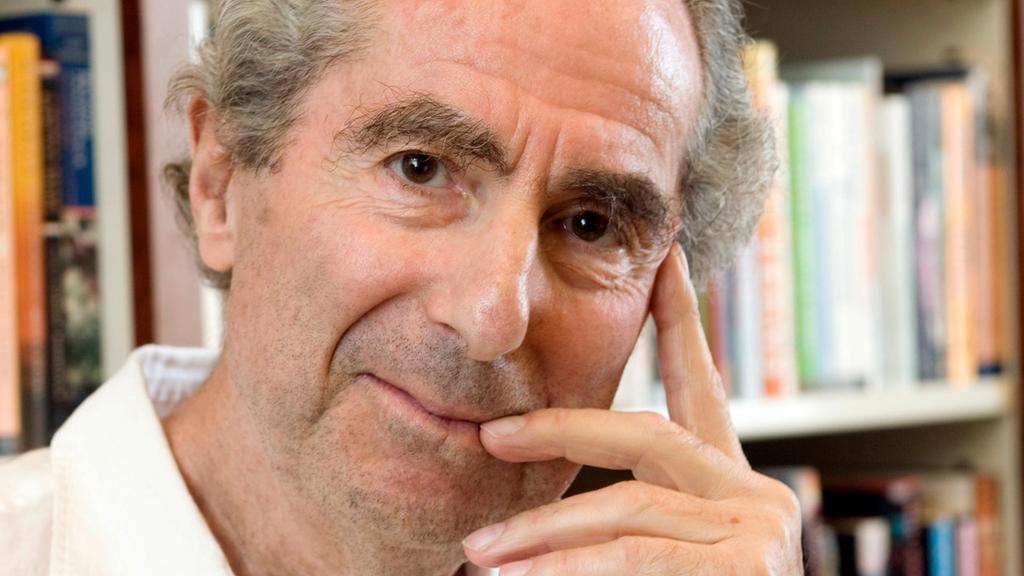

When Philip Roth, who died yesterday, was pondering his life as the 85-year-old elder statesman of American literature earlier this year, he told The New York Times that it was a matter of some astonishment and pleasure that he found himself still alive at the end of each day. Not so he could write more of his self-conscious, socially-aware, political and playful fiction – far from it. In his last collection of non-fiction he said that he gave up novels in 2010 because he had “a strong suspicion that I’d done my best work”. He was just enjoying reading history books, going to the theatre and seeing his friends.

He no longer, he said, had the mental vitality or verbal energy to “sustain a large creative attack” on a structure as demanding as a novel. Which wasn’t just a refreshingly honest appraisal of his life, but a hugely telling comment on his feelings towards the importance of the novel.

After all, Roth had by most measures become synonymous with The Great American Novel, the idea of a crucial piece of fiction that shines a light on America. It has a lineage from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick through John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath to Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. And in 1997, it was Roth’s American Pastoral that sat comfortably in that oeuvre, setting Jewish-American Seymour Levov’s upper-middle-class life against the social and political turmoil of the 1960s and the Vietnam War.

The period between John F Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974 were years that Roth once said were “alive with the horror of war, alive with the menace and comedy of the sexual revolution, alive with resistance to authority”.

“I wanted to get all that into American Pastoral,” he said. “And I think I did. I don’t know any more that’s useful that I didn’t put in that book.”

In just a couple of sentences in that short explanation, Roth nailed his craft. Right from his 1969 breakthrough, Portnoy’s Complaint, he revelled in exploring the complex matter of his Jewish-American heritage, in ways that often seemed almost confrontational. That first novel caused huge controversy for its explicit content but was laugh-out-loud funny too, as Alexander Portnoy – “a lust-ridden, mother-addicted young Jewish bachelor” – is caught between extreme desire and his Jewish upbringing.

Was this thinly veiled autobiography a confessional, even? Roth has always railed against that accusation, although he created quasi alter egos for himself – such as the writer Nathan Zuckerman who appears in many later novels – and even included a character called Philip Roth in Deception (1990). Writing, for him, was about knowledge rather than direct experience, and the creative boundary between the two was where Roth liked to reside. Indeed, at Zuckerman’s funeral in Roth’s 1986 novel The Counterlife, the eulogist says: “Contrary to the general belief, it is the distance between the writer’s life and his novel that is the most intriguing aspect of his imagination.”

Certainly, Roth wasn’t particularly at ease with being a bestselling novelist. “Fame is a worthless distraction,” he once said, refusing all public appearances post-Portnoy and disappearing to Czechoslovakia in search of Franz Kafka and deeper literary meaning in the mid 1970s. He found it in the writers producing banned work behind the Iron Curtain, and although it took some time for the effects of these experiences to percolate meaningfully through to his work, by American Pastoral his books were a combination of his interest in the broad sweep of major historical events and how they affect the individual.

After the Vietnam War setting came the McCarthyism of I Married A Communist. The Human Stain used the backdrop of Bill Clinton’s impeachment to explore American academia and he wrote about fascism in 2004’s speculative novel The Plot Against America, an alternative history in which Charles Lindbergh is elected US president in 1940 and sides with Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

In the hours since Roth’s death, many have suggested The Plot Against America should be required reading in the Donald Trump era – indeed, since Trump’s ascent to president it’s a book many have returned to, celebrating its prescience.

Earlier this year, Roth told The New York Times he wasn’t so sure the comparisons held water – simply because although “Charles Lindbergh may have been a genuine racist and an anti-Semite and a white supremacist sympathetic to fascism, he was also – because of the extraordinary feat of his solo transatlantic flight at the age of 25 – an authentic American hero 13 years before I have him winning the presidency. Trump, by comparison, is a massive fraud, the evil sum of his deficiencies, devoid of everything but the hollow ideology of a megalomaniac.”

Even in this sentence, Roth’s glee in the power of the written word is evident – whether you agree with him or not. Many don’t, of course, and for all his literary achievements it must be noted white men using their position and status to exert sexual authority is a recurring theme in Roth’s fiction.

Reading his work in a post Me Too world can feel troubling, although Roth argued that he was actually depicting men as they are, not as we would like them to be. “I haven’t shunned the hard facts in these fictions of why and how and when tumescent men do what they do,” he said.

And that’s Roth’s nuanced work in a nutshell: uncompromising, sometimes uncertain, joyful, disruptive and exhilarating.