Close your eyes for a second and think of a loved one, a familiar place; even, say, a favourite Harry Kane goal. They all seem indelibly marked on the mind – but it requires a step back to realise that you don’t actually see those images when you think of them. There is no hard drive of pictures in your head to scroll though and click on – just billions of neurones. Contrary to accepted theory, then, the world does not exist in the brain. Consciousness is, instead, the experience of the world that surrounds our body and the objects we encounter. At least that’s the theory of psychologist Riccardo Manzotti – the “spread mind”, as he calls it – and it changes the way novelist Tim Parks appreciates life.

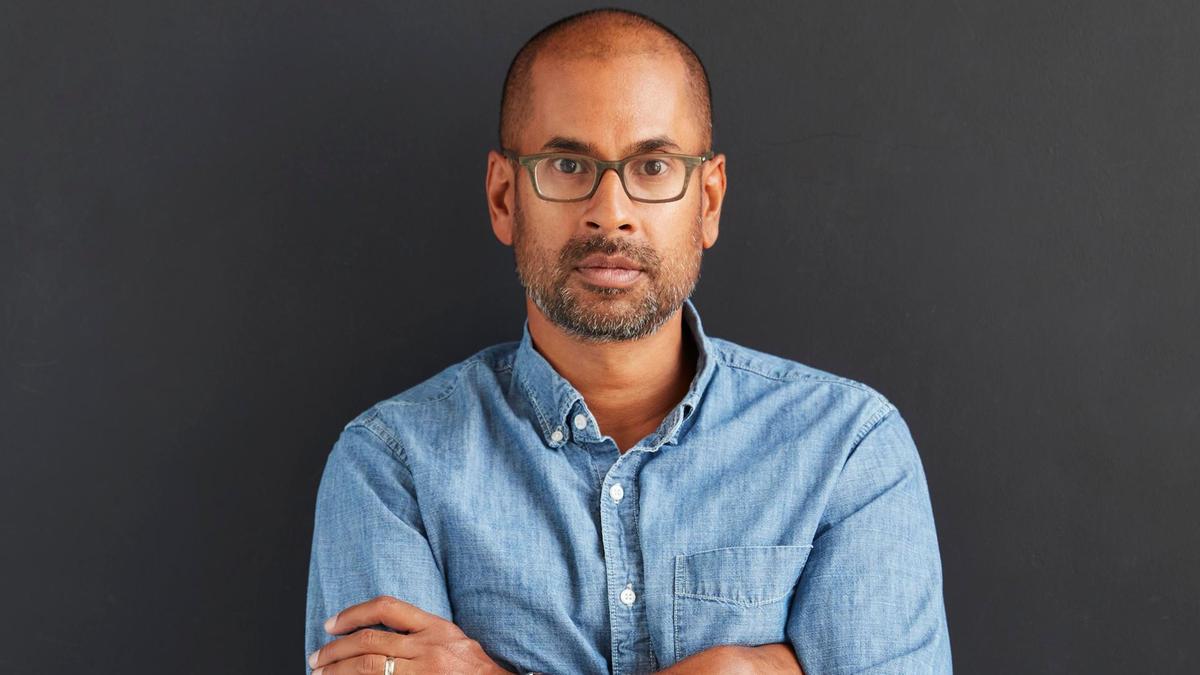

Consciousness is weighty philosophical and scientific ground, yet Parks plots a chatty, accessible path through impenetrable academic papers and conferences on his quest to understand more about being human. So chatty, in fact, he often has conversations with himself, making Parks an even more likable guide to these lofty concepts. He’s not afraid to question some of Manzotti’s more ridiculous ideas, and muses on everything from the meaning of a midlife crisis to the much-loved Pixar film Inside Out, in which five cartoon emotions battle for control of the heroine’s psyche.

Even when Parks is disagreeing with neuroscientist David Eagleman’s popular TV series and book The Brain: The Story of You (which argued that colour, smell, sound and taste don’t exist but are inventions of the brain), the approach is one of bafflement. If you suck a mint, says Parks, the experience is surely in your mouth, but contemporary science tells him it’s in his brain.

You get the sense that Parks would love a good intellectual battle with Eagleman about all these ideas, and Out of My Head often feels like a dinner party conversation about to go over the heads of nearly everyone in the room. For all his considerable restraint, even Parks ends up deep in theory by the end – although it sounds poetic in his hands. “Every time you moved your eyes,” he writes, “the world happened anew.”