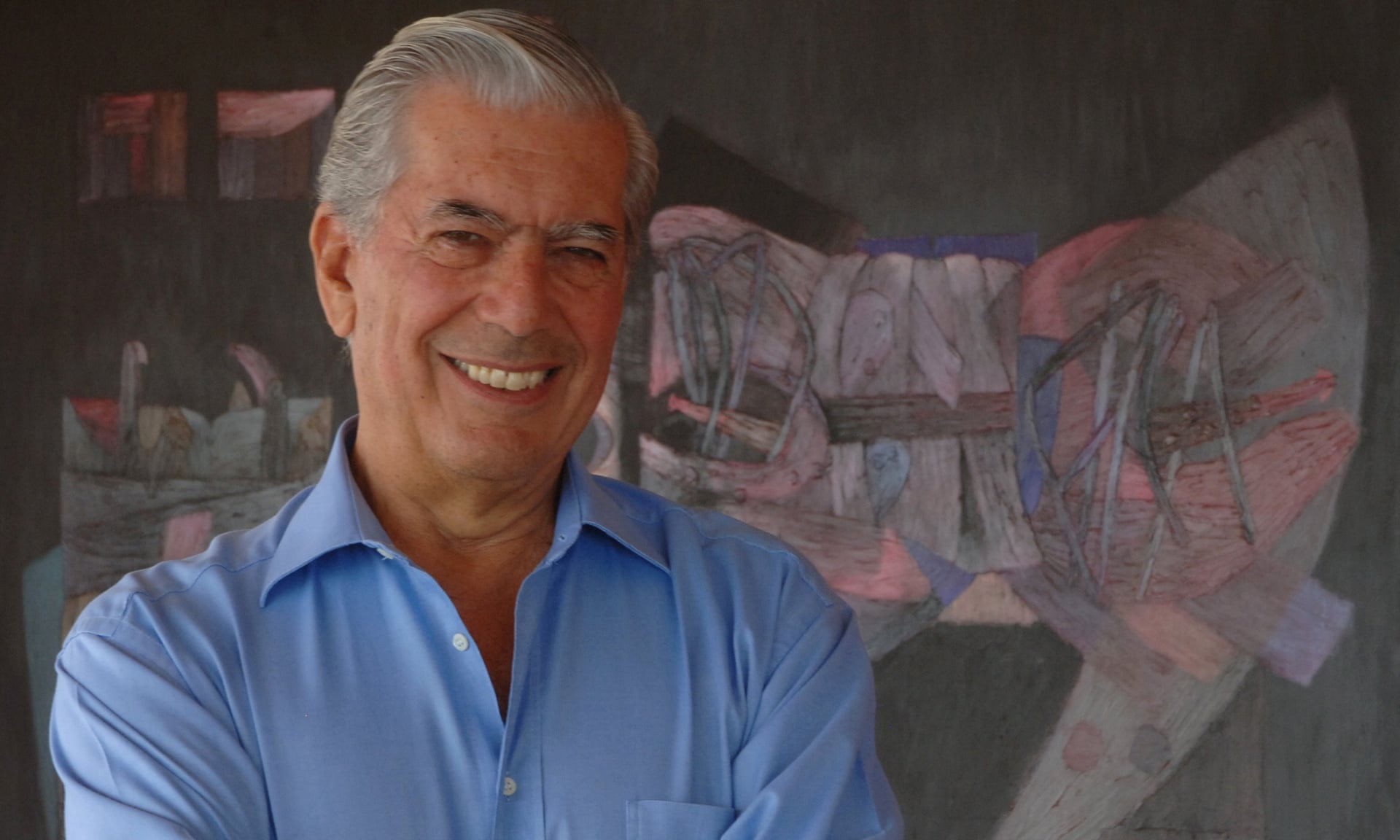

Is Mario Vargas Llosa the raciest Nobel laureate? For all the commitment to experimental, surreal, political, historical or plain comic writing that has characterised his fiction, he’s most consistently a chronicler of the carnal – and at 82, the Peruvian writer shows no sign of slowing down. The opening exchanges of The Neighbourhood, where best friends Marisa and Chabela are in bed in 1990s Lima, are so floridly graphic – translator Edith Grossman trying her best to navigate Llosa away from the Bad Sex award – that reading them in public may cause some heat under the collar. Still, if you want to know how to “throb in a time without time, so infinite and intense”, then Vargas is your man.

Marisa and Chabela are both happily married, to Enrique and Luciano, living comfortable lives attended to by butlers and maids, as they take Italian classes, go to lunch and relax at the movies. Their worlds are about to be turned upside down, however, and it’s such soap operatics that lend The Neighbourhood its atmosphere of an X-rated telenovella. Enrique is a rich industrialist and when he is blackmailed, after photographs are circulated of him at an orgy, it sets in motion a chain of events that leads to a tabloid exposé, murder, political corruption and, for no particular reason, a steamy, 17-page threesome.

It’s easy to scoff, but Llosa has recently argued that this was normal for 1990s Peru. The terrorism, President Fujimori’s authoritarian regime and the curfew he imposed made people live for the moment… and indulge in the odd sexy sleepover. So in that sense The Neighbourhood does actually fit neatly into one of the running themes of Vargas’s work, where sexuality, politics and human nature are intertwined.

Llosa actually stood against Fujimori in 1990 and here he pulls no punches in decrying the regime, which bred characters such as the menacing head of the secret service, Vladimiro Montesinos. Known as “the Doctor”, this real-life character plays a key role in the whodunnit element of The Neighbourhood, after Enrique is accused of ordering a revenge attack on the editor of Exposed magazine. His guilt is an easy assumption to make: Enrique’s family has been humiliated, his social standing destroyed by the front-page pictures of him cavorting naked with prostitutes.

The “yellow press” are consistently derided here, which, given Llosa has form for both criticising and appearing in them himself, is hardly a surprise. But – and this is where his novel does attempt to play with our expectations – the moneyed classes obsessed by their sex lives don’t have our sympathies either. There’s something faintly ridiculous about Enrique emerging from his brief stay in the marital doghouse to be quickly forgiven by his wife, gently mocked and then rewarded by more energetic sex and nice holidays in Miami. Llosa doesn’t make it explicit that there has actually been a cost to Enrique’s exploits, other than being forced to pleasure a bad guy during his one night in prison.

Instead, the heroic acts are committed by fringe characters who are barely surviving in Lima’s impoverished neighbourhoods and they eventually use Exposed for political good. It’s a shame, though, that these characters, especially the journalist Shorty and a once-famous old man called Juan, who becomes entwined in the murder plot, never really get the chance to be anything other than side-stories in a carnival of grotesques. It’s the salacious stories of the wealthy that propel what is still an enjoyable, if uneven, page-turner of a novel to its odd conclusion.

Llosa’s craft is only intermittently on display here, but he still has the power to enthral.