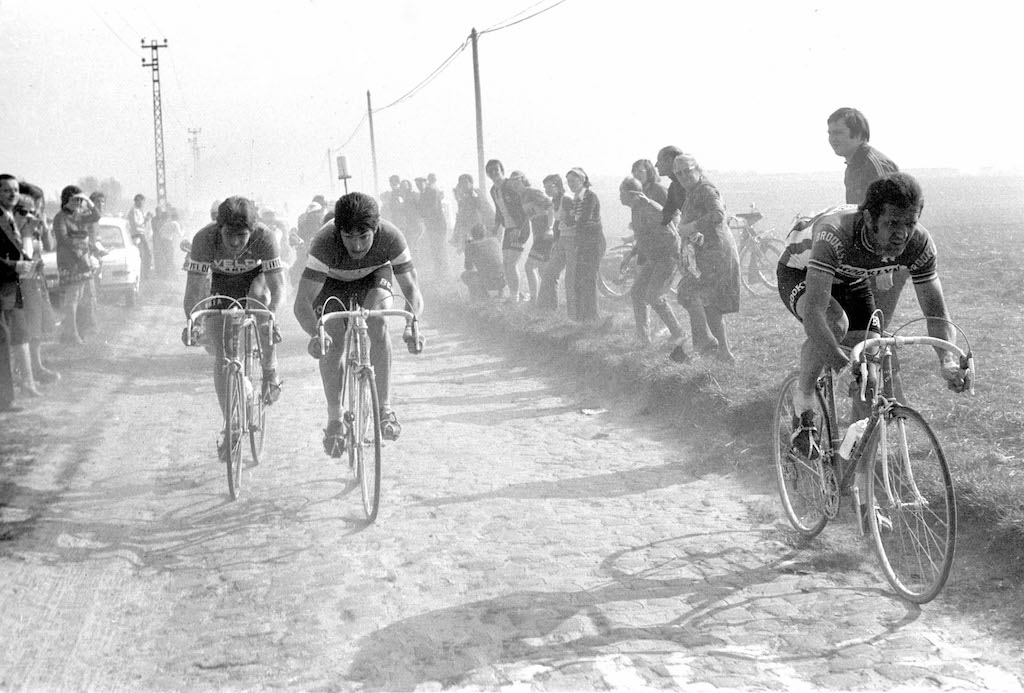

Twenty minutes into Jorgen Leth’s revolutionary film about the 1976 Paris-Roubaix bike race, Eddy Merckx, Roger De Vlaeminck, Freddy Maertens and Francesco Moser (not forgetting Marc Demeyer) finally leave Chantilly for the famous velodrome 273 kilometres and many secteurs of gruelling pave away. And on the side of the road, a father holds up his fascinated child to catch a glimpse of the men who would (or had) become legends of the sport.

Twenty minutes into Jorgen Leth’s revolutionary film about the 1976 Paris-Roubaix bike race, Eddy Merckx, Roger De Vlaeminck, Freddy Maertens and Francesco Moser (not forgetting Marc Demeyer) finally leave Chantilly for the famous velodrome 273 kilometres and many secteurs of gruelling pave away. And on the side of the road, a father holds up his fascinated child to catch a glimpse of the men who would (or had) become legends of the sport.

Watching the incredible documentary A Sunday In Hell again, this time it struck me that the child would have been about my age in 1976. The clothes – no helmets or Lycra here – the haircuts and even the Public Service Broadcast quality to David Saunders’ narration, make it feel like a completely different world. And yet, as William Fotheringham argues in his new book approaching cycling’s most celebrated one-day Classic through the lens of Leth’s extraordinary film, there is something timeless at play here too: the villages where he shot don’t look so different as the race passes through 40 years later. The small boy might this year be on the roadside with his children, roaring on Peter Sagan.

Perhaps because of its combination of contemplative long shots and concentrated close-ups Leth’s film is able to provoke such personal reflection on the passing of time and even mortality: after all, just six years later the surprise (and somewhat unwilling) winner of the race, Marc Demeyer had died from a heart attack. And it’s this richness present in A Sunday In Hell which makes what could be a slightly odd “book of a film of a race” conceit seem completely natural.

In Sunday In Hell, Fotheringham speaks to Morten Piil, the consultant who originally commissioned the film, and he calls it “a kind of heroic poem”. Leth himself wanted his film to have the quality of a novel – with the sense of an epic, unpredictable mission – rather than document a straight record of what happened and who won. That means, alongside the sheer chaos of riders picking their way through dusty cobbles and striking print workers, we also see the preparations in almost fetishistic detail, an empty town square waiting for the circus to descend, packed bars straining to hear news of who leads the breakaways, a man painting the Velodrome with sponsors’ logos. Fotheringham skilfully contextualises both the mayhem and quiet grace of the film – there’s a lovely anecdote surrounding the chorale soundtrack and a eye-opening story of what it was really like to sit on a bumpy motorbike and capture the action close up.

He also finds a contemporary review which called it “an initiation into the mystique of bike racing” and Saunders’ expositionary narration always places the action in context. And like the film itself, Sunday In Hell is not wholly concerned with what’s going on in the race. Fotheringham takes us on deviations to other Paris-Roubaix, other Leth films, and the careers of the riders whose characters and personalities A Sunday In Hell laid bare. His is also the story of a work of art, of social history and of an entire sport on the cusp of change.

Indeed, as Fotheringham discusses in fascinating detail, A Sunday In Hell changed the way cycling both regarded and portrayed itself. When the Tour De France comes around, we are all seduced by the steady shots from a helicopter of the peloton sweeping through fields of sunflowers. Leth was the first to use the technology in A Sunday In Hell – and it would be a dozen years before it was taken up by Le Tour and became integral to the way cycling was marketed.

Towards the end of Sunday In Hell, Fotheringham speaks to Quickstep Floors directeur sportif Brian Holm. He says that as team manager of T-Mobile and HTC many decades later, he would make his riders watch A Sunday In Hell on the bus before they rode it. “When I see it I feel like riding my bike, I think ‘fuck, let’s go bike racing’,” he says. The film – and the book – certainly convey the sheer eccentric madness of Paris-Roubaix.

And would I be going to Paris-Roubaix this weekend, to stand by the cobbles and look on in thrilled amazement, had it not been for A Sunday In Hell? Probably not – but I also hadn’t considered exactly why that was before Fotheringham’s fascinating exploration of the greatest cycling film of all time.

Sunday In Hell (Yellow Jersey) is out now

[amazon asin=978-0224092029&template=add to cart]