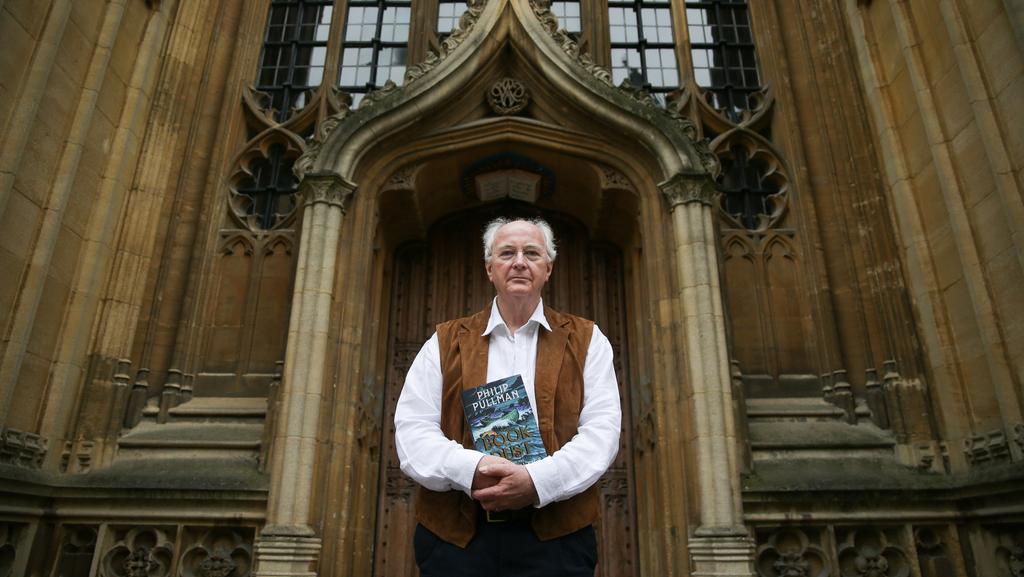

It is surely one of the most eagerly awaited books of the year. Seventeen years after the last in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy wowed children and adults alike with its richly detailed adventures of young heroine Lyra Belacqua, the 71 year-old Englishman last week published the first in his new series based in the same magical world“a universe just like ours, but different in many ways” of mechanical bears, totalitarian regimeand the Dust – of which more later – that gives the trilogy its name. The Book Of Dust is not, however, your typical children’s crowd-pleaser – and it is all the more intriguing for it.

Set 10 years before His Dark Materials begins, La Belle Sauvage revels in fruity language and explores philosophy and science. Pullman’s world is of the way people abuse the power afforded to them by religion – and makes a strong case for the importance of free will. Woven into these ideas is the tale of a young boy, Malcolm, and his sceptical friend Alice, who must confront an epic flood to save the baby Lyra from her wicked mother, Mrs Coulter. Along the way they meet both a fairy queen and an ex-con – who went to prison for child abuse – intent on kidnapping Lyra.

And like His Dark Materials, Pullman’s latest book is less Harry Potter than a repurposing of Milton’s Paradise Lost or Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene; a corrective of sorts to C S Lewis’s Narnia books, which Pullman has famously taken issue with.

So who is La Belle Sauvage for, exactly? At a press briefing last week, Pullman was adamant that he doesn’t specify his audience. “I have never wanted to do that. I’m grateful to have any audience at all … and I’d never give an age range for readers. I’d much rather launch it on the flood and see what happens to it.”

Still, Pullman has an extraordinary gift for being able to tap into what it is like to be a child, without patronising his readers or diminishing his characters. He puts this down to imagining things now in the same way as he did when he was young. As he said last week, “children are capable of extraordinary feats of courage, of affection and determination”, and just as Lyra in His Dark Materials travels to the North Pole to rescue her friend Roger from a secretive agency performing experiments on children – and how dark is that? – so Malcolm has to overcome the attentions of the scheming Bonneville.

When he announced the new series earlier this year, Pullman inventively called The Book Of Dust less a prequel or sequel than an “equel – it doesn’t stand before or after His Dark Materials, but beside it. It’s a different story, but there are settings that readers of His Dark Materials will recognise, and characters they’ve met before.”

“At the centre of The Book of Dust is the struggle between a despotic and totalitarian organisation, which wants to stifle speculation and enquiry, and those who believe thought and speech should be free,” he added. And within that explanation is the key to why Pullman’s books are arguably more important for children (and adults) than Harry Potter. True, J K Rowling also has a nice line on friendship, family, courage and the battle between good and evil. But Pullman’s world doesn’t shy away from children losing their innocence or falling in love. In His Dark Materials, Lyra isn’t a typical heroine – there is an element of the savage about her; she lies. Pullman has called her a barbarian.

In La Belle Sauvage he writes realistically, truthfully and metaphorically about the world we live in today – there are huge tracts on the dangers of surveillance, climate change and inequality. And yet each character has a daemon, a shape-shifting animal version of themselves and the physical manifestation of the human soul. Malcolm’s is variously a kingfisher, greenfinch and an owl to see in the dark.

And if that sounds faintly ridiculous to those entering Pullman’s world for the first time, the initiated will know that daemons are probably his finest creation of all. They are more than the notion of a fully realised imaginary friend – the way the children’s daemons change reflect the way personalities evolve as life continues; moving, as the books constantly do, from innocence to experience.

True, The Book Of Dust and His Dark Materials are fantasies, with all the connotations that the genre labours under. They have heroes who seemingly need to save the world – although Lyra in particular is given free will to do as she pleases. But to compare them to The Lord Of The Rings would not only horrify Pullman – he has called Tolkien’s books trivial because they don’t explore the big questions – but be wholly inaccurate. There is a pleasure to be had in the fantastically elaborate lands and characters Tolkien dreamt up, but little of deeper merit to grab hold of beyond battles between good and evil. Pullman’s books revel in moral and psychological questions. And having read some of the fantastical elements of a few of the Booker Prize nominees recently, it is not a huge stretch to Pullman’s work. The prose is delightfully readable without ever being sentimental. The idea of Dust – a metaphor for the consciousness and imagination that comes with self-awareness – underpins an outstanding narrative.

As he said last week, his books deal with “the question of consciousness, perhaps the oldest philosophical question of all: are we matter? Or are we spirit and matter? What is consciousness if there is no spirit? Questions like that are of perennial fascination and they haven’t been solved yet, thank goodness”.

And maybe these intricate ideas are why the film adaptation of The Golden Compass in 2007 was such a flop. His books are possibly too rich in detail and ideas to transfer satisfactorily to the big screen, but the movie was also hamstrung by underlying dissatisfaction from the American right that it introduced children to atheism. It does no such thing; the books merely question the motives and actions of people who use religion as a way in which they can abuse power. Pullman is an atheist, but his outlook is decidedly human, rooted in the delights and dangers of the contemporary world.

It will be fascinating to see where the remaining two books go next. He let slip that in the next instalment of The Book of Dust, a grown-up Lyra will be on a journey from the Levant to Central Asia, which should be fascinating. But in the second and third books the characters are adults – there is a 20-year leap from La Belle Sauvage. “It’s probably natural that it has a bit more of an adult tone,” he said last week. He also joked that La Belle Sauvage could be called “His Darker Materials … I’m more cynical, perhaps closer to despair.” Is anyone still convinced that Pullman “just writes for kids”?

The Book Of Dust Volume 1: La Belle Sauvage is out now, published by Penguin