One of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s former students is trying to explain the artist’s legacy.

“She was the East and the West, combined in harmony,” the student says in a film that accompanies the major new retrospective of Zeid’s work at Tate Modern in London.

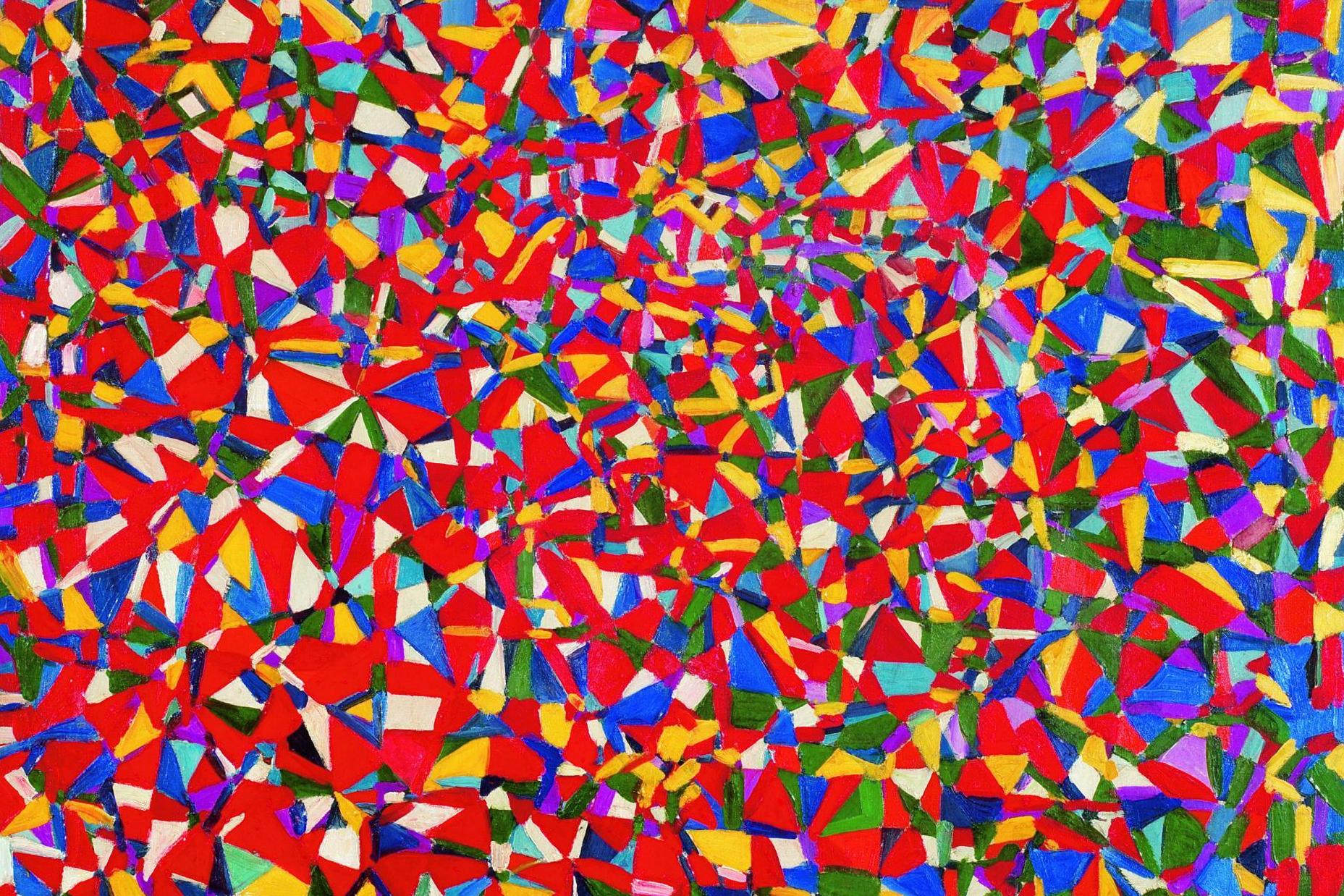

As her words bounce off the monumental canvas of one of Zeid’s most famous paintings – 1951’s My Hell – it’s difficult to argue. A vivid kaleidoscope of shapes and colours, My Hell recalls Ottoman stained-glass windows. Others might see the geometrics of Islamic art. Western critics marvel at its abstract expressionism.

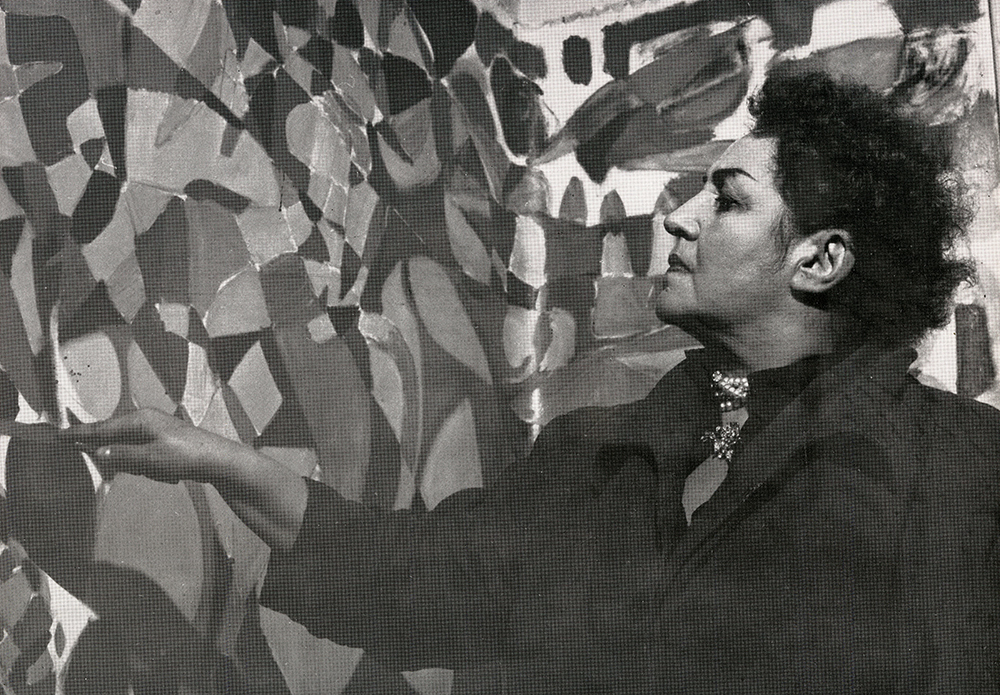

This one image sums up a show as colourful as Zeid’s 90-year life. She grew up a member of an elite Ottoman family in Istanbul in the early 20th century and became one of the first women to study art in Turkey.

Zeid was also the wife of the Iraqi ambassador in Nazi Berlin who took tea with Hitler; a figure in the post-war Paris intellectual scene; and before her death in 1991, a teacher in Amman – she even painted Donald Trump.

“She was like a sponge,” says one of the show’s curators, Vassilis Oikonomopoulos. “Taking in all sorts of influences and quickly reusing them in her own style – she’d do portraits, abstract works, often at the same time.”

It’s only now, however, that Zeid is attracting the kind of critical attention that often deserted her during her career – although she did become the first female artist to stage a solo exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1954.

“It’s astonishing that an artist of such force and originality should have been practically forgotten,” fellow curator Kerryn Greenberg writes in the exhibition’s introduction.

Maybe that was because, in her early years, Zeid had to overcome the suspicions that she was a society woman with great talent who was merely “playing” at art. Her regular stylistic reinventions perhaps didn’t help either – the disparate nature of her work making her difficult to categorise.

Still, earlier this year, another Zeid geometric abstract work, Towards a Sky, sold for US$1.27 million (Dh4.6m) at auction in London, nearly double its list price.

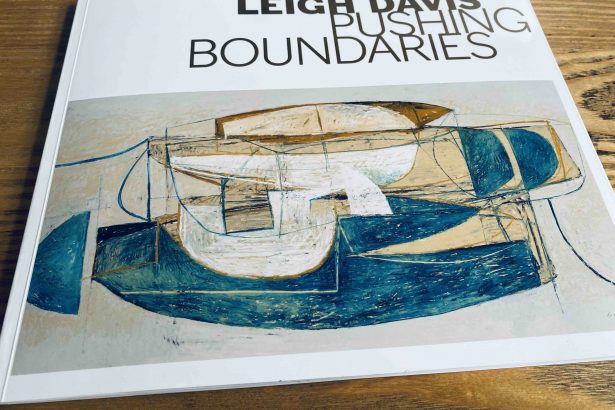

Another of her former students, Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, has just written an intriguing book about her life and work (Fahrelnissa Zeid: Painter of Inner Worlds, published by Art/Books). This exhibition is booked to go on to Berlin and Beirut following its London showing. So why has Zeid come to the forefront now?

“Well, it’s definitely time to rethink her influence on and involvement in Western abstraction,” Oikonomopoulos says, underneath one of the many paintings he has worked to bring to London. “And if you look at the different forces that impel international artists today, it’s really good to explore figures like Zeid, who had a hugely nomadic life and whose work was influenced by a number of elements.

“Somehow, she became neglected. Maybe that was partly because she was female in a male-dominated art world.”

The exhibition tells the story of how Zeid moved from watercolour portraiture as a talented teenager (My Grandmother, 1915) to grand, Renaissance-inspired compositions teeming with life and colour in the early 1940s (Three Ways of Living [War], 1943), through to the abstract work that would make her name after the Second World War.

Without question, it’s this period of her work that grabs the most attention – not least because My Hell is more than five metres wide and two metres tall – and is generally regarded as her most successful work.

But the real intrigue in this show comes with her move into abstraction in the first place. Initially, Zeid was reticent: one work is even called Fight Against Abstraction (1947) and features discernible heads and arms amid the mosaic effect. By the time she had painted the aptly-titled Resolved Problems (1948), she had fully absorbed herself into the abstract world.

“She was trained as a figurative painter and maybe it was difficult for her to unlearn all that, in a way, to leave one part of herself behind,” Oikonomopoulos explains. “But she wanted to do it. She was really interested in the ways some of the motifs of the Arab world produce a form of abstraction.”

Oikonomopoulos gestures towards one of the most unassuming works in the show, a small mixed-media offering on paper called Bedouin Women (Towards Abstract). It’s from 1950 – but its reference to 1930s Baghdad says everything about Zeid’s journey to abstraction.

“She would watch street life through the mesh of a mashrabiya, and said she saw colours and shapes rather than people,” Oikonomopoulos says. “It was an idea that she didn’t forget.

Laïdi-Hanieh is less sure of this anecdote – not least because Zeid lived in a modern concrete building in Baghdad – but it still confirms her belief that she was a painter of “light and motion”.

From the wild abstract of Basel Carnival (1953) to the 1972, Turner-esque oil of London (The Firework), there is always something vivid happening in Zeid’s paintings.

“There was often this question of whether she was interested in Islamic art,” Laïdi-Hanieh says. “But actually she was obsessed by the cosmos – she once said to one of her students that: ‘The universe is always moving, so why do you paint these static lines and shapes?’”

Which is why the Tate’s assertion that Zeid was someone who “fused Byzantine, Islamic and Persian influences with European approaches to abstraction” is possibly the only misstep in what is otherwise a fascinating exhibition.

For Laïdi-Hanieh, Zeid was less calculated than that. “I can say for sure that she didn’t willingly appropriate Islamic art, or any art form. She didn’t ‘modernise’ in that way. Her work was quick, expressionist. When she saw everyone doing abstract art in London, she figured: ‘Why not? I’ll give it a go.’

“I love the way her spirit then takes over and you get this sense of speed and movement.”

As someone who came into Zeid’s orbit as a teenager and has continued to be fascinated by her work, Laïdi-Hanieh is better placed than most to explain why the Tate show is so important.

“It’s a wonderful way to introduce people to Fahrelnissa, like a Greatest Hits,” she says. “She’s getting her due at last.”