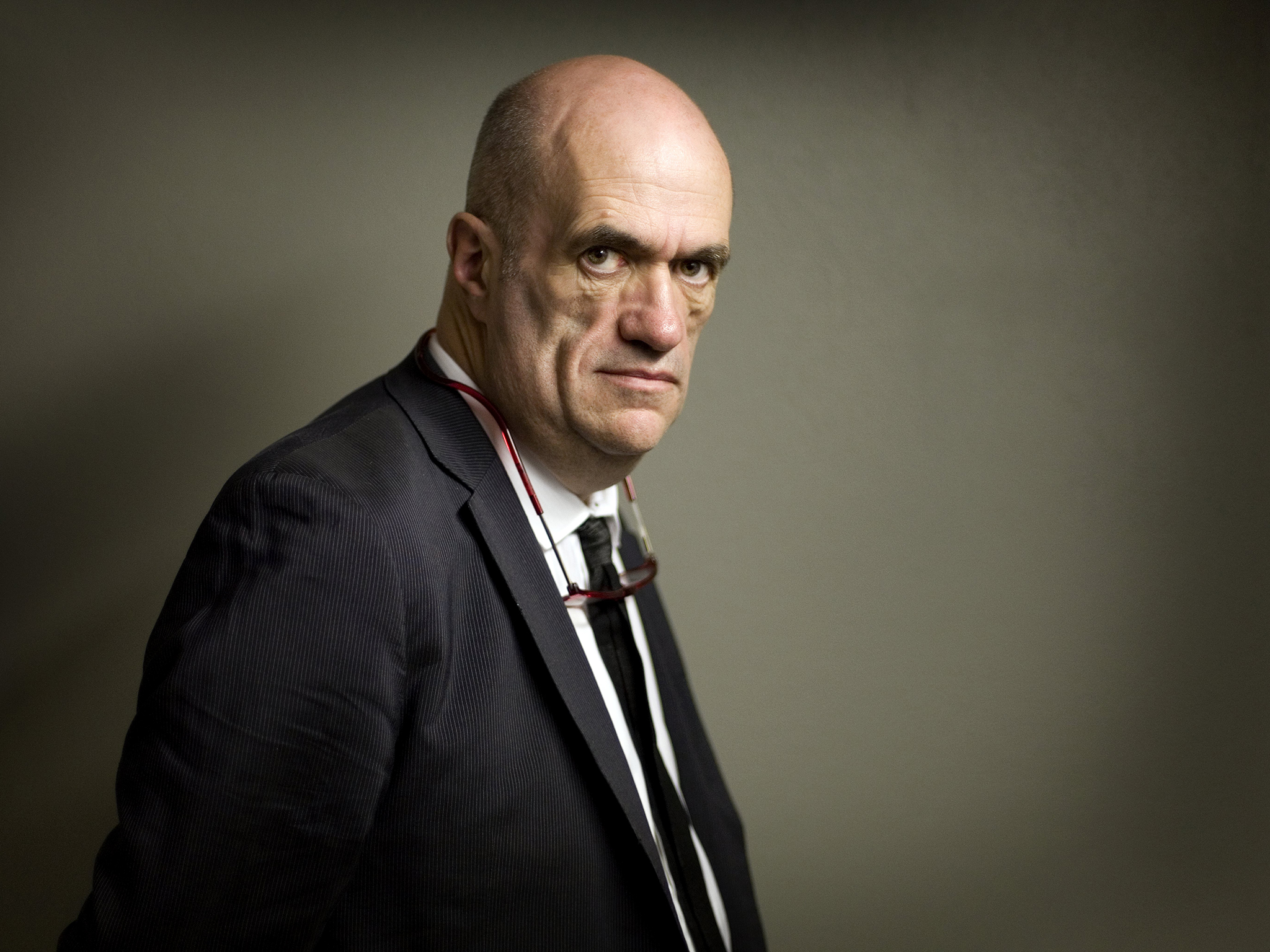

As opening lines go, “I have been acquainted with the smell of death”, is about as intriguing as it gets. But then, in his latest novel, Irish author Colm Tóibín is navigating some of the most powerful stories of all time.

House of Names is a retelling of the Greek myth of Clytemnestra, and to describe it as bloodthirsty, vengeful and tragic are all understatements.

For those unfamiliar with the ancient tale, Clytemnestra is the wife of Agamemnon, warrior king of Mycenae. He sacrifices their daughter Iphigenia, which leads a deceived Clytemnestra to plot to kill her husband in rage. She then becomes ruler of Mycenae. But their other daughter Electra is horrified by her mother’s actions and, with her brother, Orestes, plots to take the ultimate sanction.

There is no “happily ever after” in this tale, unless there is a satisfaction in revenge.

The brilliance of House of Names is that prior knowledge of a myth which takes such a central role in Sophocles’s and Euripides’s most enduring plays is by no means a plot-spoiler for the novel.

Tóibín turns this story into equal-parts gripping thriller, an exploration of friendship and exile, and a commentary on family and religion. It feels modern and contemporary in tone and approach; the pace of the prose matching the never-ending bloodshed.

Tóibín makes Clytemnestra a calculating villain but offers an outraged empathy for her pain. He tells the story from Orestes’s and Electra’s points of view, too, which means he is able to justify, or at least explain, everyone’s actions.

When Leander pleads with his friend Orestes, “the only thing I know is that we must not kill anyone else”, there is sympathy for his doomed desire to avoid more bloodshed. All of which makes this a human tale, rather than one in which people are just doing the gods’ bidding.

This neatly links House of Names with Tóibín’s Booker-shortlisted novel The Testament of Mary, a reimagining of the story of the mother of Jesus. In fact, much of Tóibín’s work features conflicted, unpredictable mothers. Clytemnestra certainly qualifies.

In less accomplished hands, retelling Greek myths might seem like a writerly challenge, something to admire rather than love. But Tóibín, while clearly enjoying the landscape of ancient murder, teases out new resonances and meanings.

House of Names is terrifying, horrific and angry. It’s also quite extraordinary.