It begins with a beheading. Then another, and another, until nine severed heads are found in a sleepy Iraqi village. It’s a shockingly vivid introduction to the violent, chaotic world of Muhsin Al-Ramli’s The President’s Garden.

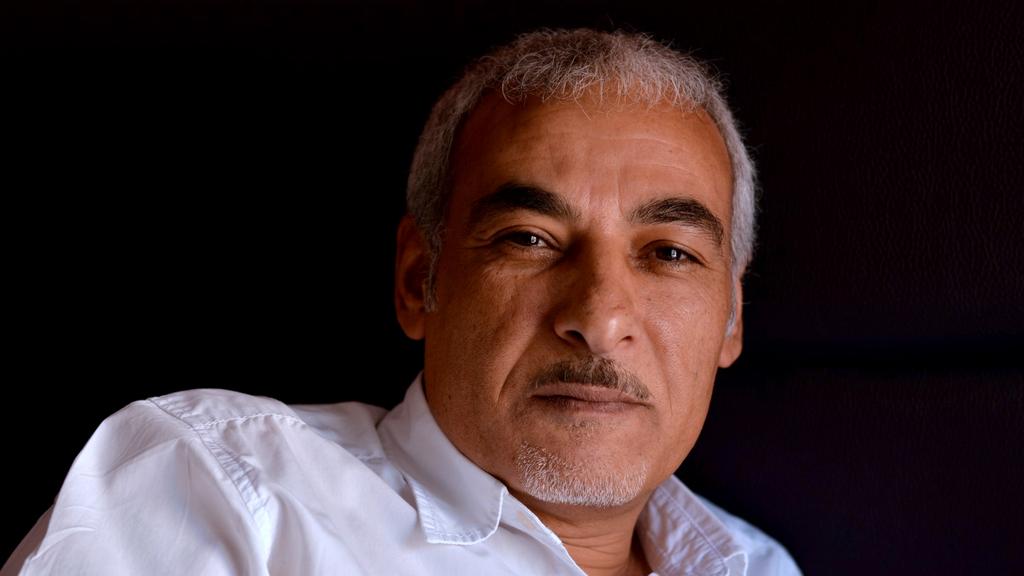

Asking where the Iraqi novelist got his inspiration seems an innocent enough question. Nothing prepares you for the answer.

“On the third day of Ramadan in 2006, I received news of the slaughter of nine of my relatives who were fasting,” Al-Ramli says. “My village found their heads in banana crates, along with their ID cards, on the side of the main road near my family’s house.

“That news shocked and terrified me. I wept. I had childhood memories of playing with the owners of these heads.”

Understandably, Al-Ramli had no idea what to do, other than to take refuge in something he knew: writing. Six years later, The President’s Gardens was published in Arabic, framing the stories of friends Abdullah, Tariq and Ibrahim around both their personal tragedy and the tragedy of Iraq in the years between the war with Iran and the aftermath of the American invasion.

It was longlisted for the 2013 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, and this week an English translation, by Luke Leafgren, is finally published. It is a stunning achievement.

“I wanted to say that the victims were not just numbers to be tallied up in newspapers, but each was an entire world in themselves,” he says of his aims for the book.

“They were people with families, memories and dreams, and it was the ugliest injustice to slaughter this entire world and forget it so nonchalantly in a matter of minutes.”

For all that death is ever present in Al-Ramli’s book, his real achievement is to make the characters of Tariq, Ibrahim and Abdullah so full of life, believable and even relatable. Their relationships somehow endure despite the heavy toll of simply living in Iraq.

“That’s the relationship that victims have with each other,” says Al-Ramli.

“They are examples of common, everyday people, the pattern for millions of Iraqis upon whom injustice has fallen. They pay a heavy price on account of the dictatorship, the customs, the traditions, the wars, the sanctions, and so on – all without having any guilt or any choice in the matter.”

Abdullah’s journey gives the book its title: he ends up tending the Iraqi president’s sumptuous garden – but of course digging holes in the Earth is not as innocuous a task as it might seem under his rule.

It’s interesting that Saddam Hussein’s name is never mentioned, which has the effect of allowing The President’s Garden to work as a comment on any totalitarian regime.

“Yes, that’s right,” Al-Ramli agrees.

“Except there is also a personal reason: I do not want to mention Saddam Hussein by name in any of my literary works, he being the one who killed my brother and many of my relatives.

“I feel that doing so would pollute my texts. In my works, you might find names for everything – even for a donkey – but you won’t find his.”

Al-Ramli fled Iraq for Jordan after “three nightmarish years in the Iraqi army”, then left for Spain in 1995, where he lives now.

There is a chilling line in the book that seems to sum up what it must have been like to live through that period in lraq, as Abdullah tells Ibrahim: “There’s no way that death could be worse than life”.

“When the Iraq-Iran War began, I was 13 years old, and the corpses of the slain arrived every day,” says Al-Ramli.

“Death has continued without a pause until today, for my village has been under the control of Daesh for two-and-a-half years.

“Because of the multitude of ugly ways to die in Iraq, most people longed for a natural death – indeed, I heard my mother pray to God that he would make her die.

“I myself longed for death numerous times.”

While he has suffered more than most of us could imagine in our worst nightmares, somehow The President’s Gardensmanages to celebrate the humanity of its protagonists.

“There’s no life without hope,” Al-Ramli reminds me, and the possibility that Leafgren’s translation might now reach a much wider audience is a thrilling chink of light.

“It will bring the voices of my people, along with their sufferings, to the greatest number of people in the world,” he says.

“The sense among victims that others know and feel their pain will ease that suffering and let them feel a kind of human solidarity.”

The book also ends on a “to be continued”, and Al-Ramli reveals he is halfway through a sequel. Its tone might surprise a few people.

“I believe the sequel will be more enjoyable, more suspenseful,” he says.

“I will make the reader laugh more than cry this time, not because what happens is funny, but because when tragedy reaches its most painful climax, sometimes there is nothing we can do after the tears except laugh.”