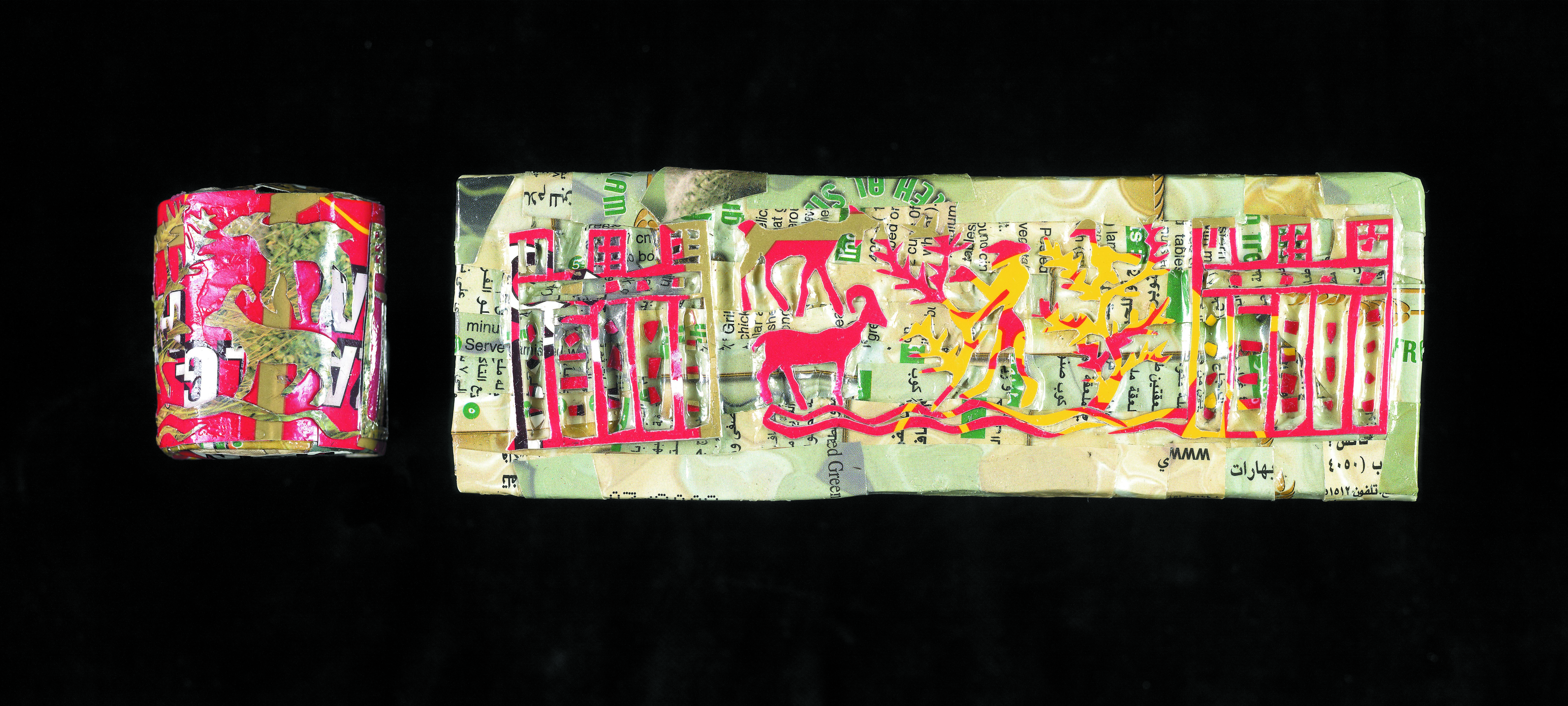

Bahman Mohassess (1931–2010), paper collage, 2009. © The Trustees of the British Museum

In the same week that the British Museum announced plans for a major new gallery dedicated to the Islamic world, news began to filter through that ISIL militants were tearing apart ancient cities in Iraq full of priceless artefacts, manuscripts, sculptures and buildings.

As Venetia Porter, the lead curator of Islamic art at the British Museum, marvels at the beautifully detailed archaeological finds from Samarra in Iraq in the British Museum’s current display, the irony is not lost on her.

“I’m hesitant about making a direct link between the two stories,” she says. “What’s happening there is so utterly horrendous that it’s difficult to know what to say. But what I do know is that now is an important time to show that the cultures of Islam are deep, rich, relevant and fascinating.

“They have this broad sweep from Africa, right through the Middle East to the Malay world. And we have to make sure we’re representing them properly.”

To that end, in 2018 the British Museum will dramatically increase not only the floor space available to show its collection of work dating back to the seventh century, but its engagement with audiences, too.

“Look at this enamelled glass canteen from the 13th century,” says Porter. “I love this – it’s from Syria or Egypt, and its Arabesque design is classically Islamic. But St George and the dragon is on there, too, which is of course a very important story in both western and Islamic cultures.

“European craftsmen really wanted to emulate this technique on glass, but they had to be taught it. To me, this small canteen encapsulates everything we want this new gallery to be. It tells the stories of our interconnectedness.”

Porter could spend all day picking out stories like these from the ceramics, metalwork, glass, stuccos and artworks that make up the British Museum collection. The problem is, not everyone gets such an engaging, personal tour of the current John Addis Gallery. They have to make do with small labels next to plates and vases, usually behind glass. So the intention is to make full use of what the gallery has available to tell themed, chronological narratives about the art and culture of the Islamic world, backed up with extra material accessed by smartphone or tablet.

“For example, if we have a decorative tile made in medieval Iran, we want to be able to tell people what the building was like that it came from, what its inscriptions say,” says Porter. “Learning about the places these objects came from is really important.”

And though the British Museum is very much a history museum, the stories don’t stop with the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. The British Museum owns work by the conceptual artist Michael Rakowitz that could be displayed (pictured below), and the intention is to make targeted acquisitions that continue to reflect contemporary cultural concerns.

“That’s an area I feel very passionate about because I can completely see the continuum,” says Porter. “You can look at this region from the pre-Islamic era right up to now – we’ve called it different things but it’s basically the same place generating art.

“What I love about the contemporary work is that so often the artists are really engaged with the world they live in. So they’re looking at religion, history and politics, and they articulate their concerns and interests through art.”

None of these plans for 2018 would be possible, however, without the financial backing of the Kuala Lumpur-based Albukhary Foundation. Porter first dealt with the organisation in 2004 after her exhibition Mightier Than the Sword, which told the story of Arabic script through objects, toured Kuala Lumpur’s Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, of which Syed Mohamed Albukhary is a director. The foundation’s patronage also gives the British Museum a certain amount of authority – Porter worries that “none of us in the museum world have really worked out how to properly represent living Islam”.

Actually, recent history suggests that the British Museum is more skilled than most. Its touring exhibition Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam won an award last month from the Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation and the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies for promoting greater understanding.

Its success is a tantalising taste of what the new space – to be called the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World – might feel like in three years.

“We had so many visitors to the Hajj exhibition, and it was successful because it mixed historical objects with contemporary work to tell a story,” says Porter. “We were so thrilled with the response, which came from all sorts of people.

“Museums like ours shouldn’t ghettoise, they should emphasise how interconnected we all are. So I hope that by 2018, we’ll be able to open people’s eyes and show that we all share much more than we think we do.”