A Moroccan man missing for 26 years, a Cairo-set psychological thriller and a journey into a more stable Iraq are just some of the stories on the fascinating International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) shortlist this year. The winner will be announced at an awards ceremony in Abu Dhabi tonight, so we caught up with the six nominees from Egypt, Morocco, Syria and Iraq and asked them to tell us about their books, their writing careers and what it means to be shortlisted.

Inaam Kachachi for Tashari

Kachachi is an Iraqi author enjoying her second IPAF shortlisting after being nominated in 2009 for The American Granddaughter. She is the only woman to make it through to the final six this year.

On the novel: “The novel is an attempt to observe what Iraq was like and what it has now become. A society struck by destruction as it lay asleep, forcing millions of Iraqi refugees to scatter to the four corners of the Earth.”

On being shortlisted: “It is a sign of interest in the large number of Iraqi novels that have been published in recent years. Perhaps the importance of the prize lies in the media’s interest in it and also its neutrality when it comes to the nationality, sex and age of the writers.”

On her writing career: “I am an aged journalist and a young writer. I wrote short stories that were published in Iraqi and Arab magazines and started writing novels late. Through them I could express more clearly my inner scream of protest at the destruction of my country.”

Abdelrahim Lahbibi for The Journeys of ’Abdi, Known as Son of Hamriya

One of two Moroccans on the list, Lahbibi has come to novel writing late, after a life working in education.

On the novel: “The novel begins with a manuscript which a researcher rescues and rewrites, making it a travel narrative as ’Abdi journeys from Morocco to Saudi Arabia, and an investigation into the strange story of ’Abdi in different places, worlds and times.”

On being shortlisted: “It is an encouragement to continue being creative, to create new types of novel that combine international modern forms and the arts of traditional Arabic narration. And in so doing, develop an Arabic novel which resembles ‘us’.”

On his writing career: “At the beginning of the 1970s, I was engrossed by the idea of writing a novel. It was risky, since I chose my life story as the subject and it was full of tragedies, setbacks and disappointments. So I didn’t do it. I only found myself, the paper and the pen again at the beginning of the 21st century. The ink flowed.”

Youssef Fadel for A Rare Blue Bird That Flies with Me

The oldest writer on the shortlist, Fadel’s packed life includes imprisonment for his political beliefs in 1970s Morocco to becoming a playwright, screenwriter and Grand Atlas Prize winner in 2000.

On the novel: “Aziz leaves his house the morning after his wedding to Zina and doesn’t return for 26 years, nearly 20 of them spent in prison. Zina has spent the same amount of time searching for him and after a stranger presses a scrap of paper into her hand, she undergoes the hardships of one last journey.”

On being shortlisted: “It is an acknowledgement of my work. I have spent decades in a place between despair and expectation, working as though I was digging into rock. It is also a win for the Moroccan novel.”

On his writing career: “I wanted to be an artist or a writer ever since I was a child. I also loved the theatre and read many plays. So I became a playwright and wrote for big companies. But all my imagination, desires and leanings were always towards novel-writing.”

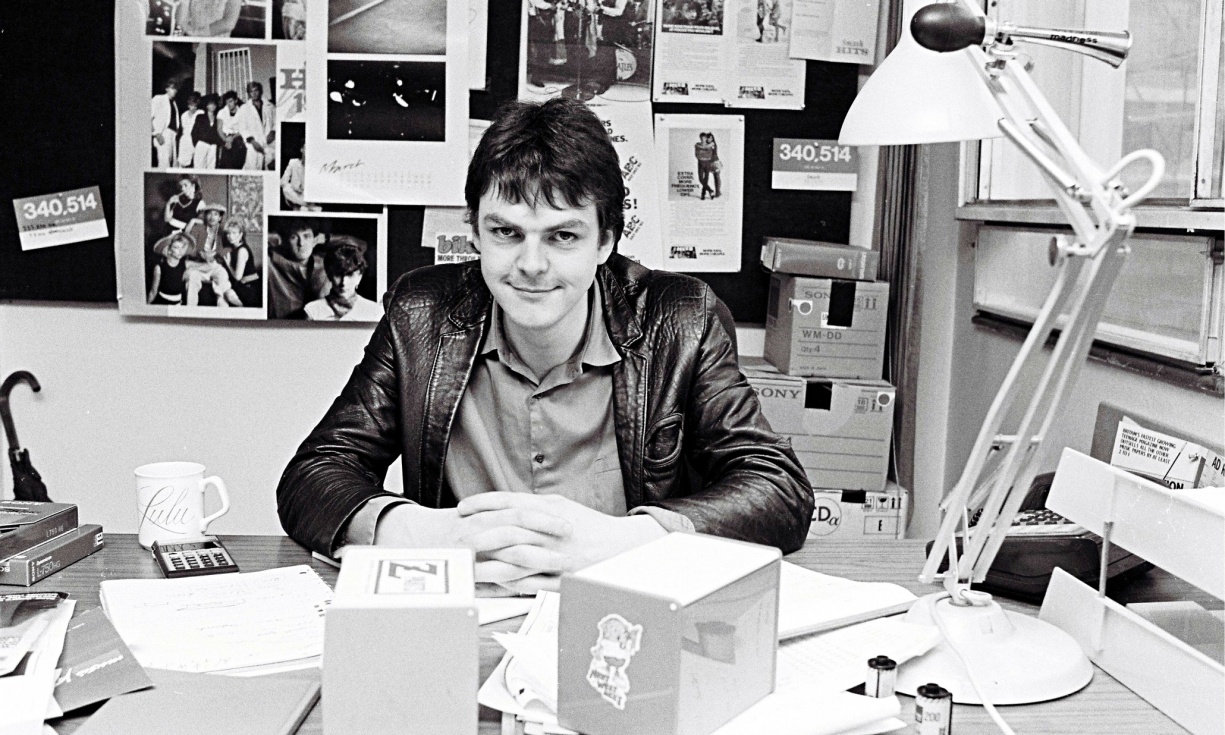

Ahmed Mourad for The Blue Elephant

Mourad is the youngest novelist on the shortlist, born in Cairo in 1978. An award-winning short filmmaker, his first novel, Vertigo, was adapted for television in 2012.

On the novel: “It’s a novel that tackles taboos and poses questions about the nature of relationships in Arab society. What is true love? Forbidden passion, magic? All these appear within a framework of hallucinations that make the reader an active participant in the events of the book.”

On being shortlisted: “It means that the novel has succeeded both in the Arab world and beyond. Reaching the shortlist is a great honour. However, it means I need to work hard to keep at that level. The prize can create a momentum in Arabic literature, taking the novel to new horizons and to new readers.”

On his writing career: “I actually studied cinematography, but my personal goal is to try to return reading to its exalted place in the hearts of human beings. To make it an important habit that people don’t give up as long as they live.”

Khaled Khalifa for No Knives in This City’s Kitchens

Born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1964, Khalifa is a screenwriter, journalist and novelist. His previous book, In Praise of Hatred, was shortlisted for the IPAF in 2008.

On the novel: “It is about the pain of Syria. Through the life of a family who make the belated discovery of how much their lives and their city have been devastated, it tries to answer the question of how Syrians lived in the shadow of oppression and a one-party state.”

On being shortlisted: “It means happiness to me. Since its beginning, the prize has been important because it has brought needed publicity and attention to the novel and novelists. It is a rock thrown into a stagnant pool.”

On his writing career: “Quite simply, I am a Syrian writer and other titles do not tempt me. I have spent most of my life writing and in defending my literary project. I am only concerned with writing a good novel.”

Ahmed Saadawi for Frankenstein in Baghdad

An Iraqi poet, screenwriter and novelist, Saadawi is a graduate of 2010’s much-vaunted Beirut39 project, which sought to celebrate the best young Arab authors. Frankenstein in Baghdad is his third novel.

On the novel: “The novel attempts to imagine some decisive events that happened in Baghdad in 2005, to look into the reality of violence in Iraq today. All this occurs within a bundle of interlinked stories that work on two levels: fantasy and reality.”

On being shortlisted: “It represents an acknowledgement of the artistic achievement of this novel and on a more general level, it honours Iraqi novel writing – which has made important progress. The prize has helped the novel achieve big sales across the Arab world, which is something aspired to by most novelists.”

On his writing career: “My literary efforts began with poetry in the mid-1990s and I published several booklets of verse as well as continuing to draw, especially comics and cartoons. As well as the novels, which came later, I have written several dramas for television, short films and documentaries.I love variety in my work – I find it enriching.”