Great to see Hassan Blasim’s short story collection The Iraqi Christ on the longlist for the 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize . It seems like a long time since I caught up with him at Manchester Piccadilly, of all places, to chat about the book, which looks at the last 40 years of Iraqi history in fantastic detail – looking at the people behind the headlines.

And it was also marvellous to see Sinan Antoon’s The Corpse Washer on the list – I’m due to talk to him about a book he translated into English himself very soon.

Anyway, here’s the interview with Hassan, first published in The National last February…

HASSAN BLASIM

When the Iraqi author Hassan Blasim left his native Baghdad in 2000, the state of his country had exhausted him. “People say war is soldiers and bombs but it’s more than that,” he says. “In Iraq it’s been a constant war with your neighbour, your dictator, your society, your religion. Trying to survive is like a nightmare. Perhaps that’s why my stories turn out the way they do.”

His latest translated short story collection, The Iraqi Christ, attempts to both make sense of and poke fun at Iraq’s recent past. And Blasim is uniquely placed to chronicle what his English publishers call the “dark absurdities” of Iraq. He fled to the safer Kurdish city of Sulaymaniyah after attracting the wrong sort of attention for his anti-establishment documentaries, but even though he was among like-minded people, he found himself in danger for being Arab in Kurdistan.

So began a four-year, nomadic existence on the fringes of society in Iran, Turkey and Bulgaria. Ask him why it took so long to reach Finland (where he still lives today) to gain refugee status and the answer is simple. “I didn’t have enough money to pay the mafia to smuggle me in,” he laughs. “Writing short stories is not so lucrative.”

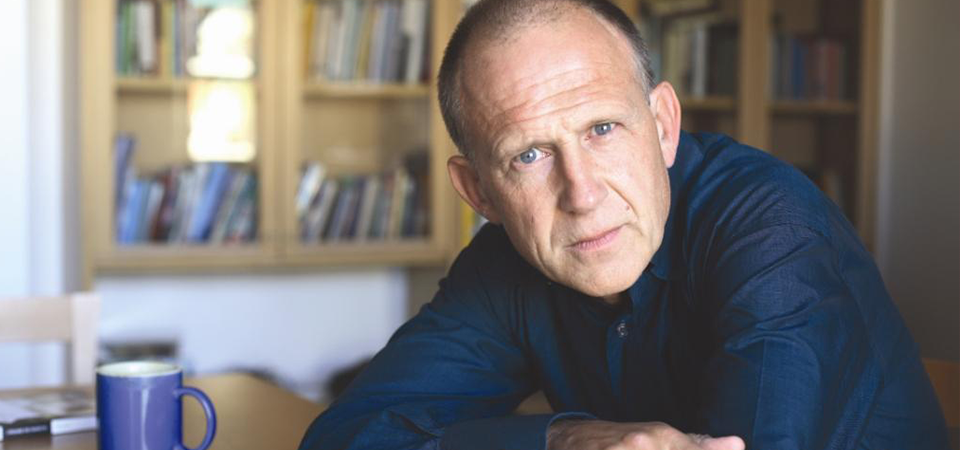

Eight years later, Blasim is on the move again but for much more edifying reasons. After an excitable review of his first translated collection, The Madman of Freedom Square, referred to Blasim as “perhaps the best writer of Arabic fiction alive”, interest snowballed. The Iraqi Christ is published next month, and when The National catches up with the ebullient 39-year-old author in Manchester, he’s at the end of a UK-wide book tour to promote it.

“It’s part two of Madman in a way,” he explains. “I mean, you can’t talk about violence, war and the last 40 years of Iraqi history in one short story collection. We are all familiar with the news stories about bombs in Iraq killing 50 people. But I found myself wanting to understand the people behind these numbers.”

Whether Blasim is the best contemporary writer of Arabic fiction is a matter of interpretation but his writing has a uniquely explosive force. In fact, the language has got him in trouble: Blasim’s work is banned in Jordan and censored in Lebanon, which, depending on his mood, is either a source of amusement (“people can read it online anyway”) or exasperation.

“People die in the street because of some roadside bomb and yet all everyone talks about is this beautiful, sentimental, poetic Arab language that I’m supposedly destroying. But who is writing about what it’s really like, about this nightmarish, unreal violence people are experiencing? So I really don’t care if it’s not literary in the traditional sense.”

There were also concerns about his attitude towards religion in Madman. Even the title of this new collection implies a certain recklessness in Blasim’s dealings with traditional belief systems. He raises an eyebrow at the suggestion.

“Look, anyone who reads my stories would immediately know I absolutely don’t attack religion. Maybe I make a few jokes about it and some don’t like that but people do talk this way in the street. It’s completely normal in Iraq. And yet when it comes to publishing what people might actually say, suddenly it’s not right.”

The title story, The Iraqi Christ, is a rather beautiful tale about the sacrifice made by a Christian, Daniel, so that his mother might live. “You know, there are two million Christians in Iraq,” Blasim smiles. “Of course what Daniel does in the end is sad but all Iraqis are like Daniel. We suffer. We give our lives. And I wonder whether the focus in Iraq is sometimes on the importance of religion rather than people.”

Such concerns are part of the reason Blasim feels it’s too soon to return to Iraq. Finland remains “a place of peace where I can talk about everything”, and he certainly doesn’t feel that the distance is a problem. “I hear the stories. I build in the fiction. I use my imagination,” he says.

Beyond all the violence and torment, the belief in the power of storytelling shines through.

“I wouldn’t say I have a big political message, actually,” he says. “But think of it like this: when you put a camera in the street in London, not that many people are interested. When you do it in Baghdad, everybody wants to come and tell their story. Doing that is so important for a country that has been through what Iraq has had to suffer.”